Mount Rainier is possibly the No. 1 geological icon of the Plateau.

Not only does the mountain continue to take away the breaths of residents and visitors alike as they drive out of the Sumner valley and into Bonney Lake, but the volcano is also responsible for the way the Plateau is shaped geologically, from the flatness of the land to the richness of the soil.

But every rose has its thorn.

The U.S. Geological Survey has named Mount Rainier as one of the nations most dangerous volcanoes, and in preparation for what could be a big eruption, Pierce County is taking steps to improve its lahar warning systems.

After the March 2014 Oso mudslide that took the lives of 43 people, County Executive Pat McCarthy requested a risk and readiness review of the mountain’s lahar warning system.

Since then, the county’s Department of Emergency Management and the USGS have been working on improvements to the system, and just completed the first installment of upgrades in late December.

Work on the lahar warning system is expected to continue through the year.

HISTORICAL LAHARS

The greatest danger Mount Rainier poses to communities like Orting, Sumner and Puyallup isn’t lava flows or ash fall; its lahars, said Carolyn Driedger, who works at the USGS’s Cascades Volcano Observatory in Vancouver, Wash.

“A lahar usually begins during a volcanic eruption when a lot – or a little – snow is melted. Enough snow to get the rock debris moving,” she said. “It’s a muddy slurry that contains everything it picks up.”

Lahars have also been described looking and acting like a river of wet concrete that picks up and destroys everything in its path.

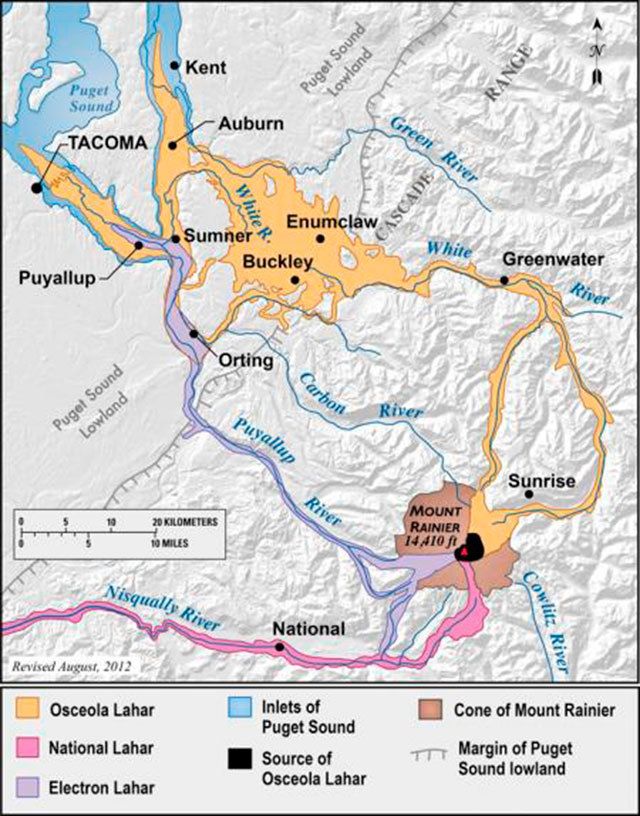

Unlike lava flows, which typically don’t extend farther than 10 miles from the summit of a volcano, Mount Rainier’s lahars have gone as far as reaching the Puget Sound, USGS research shows.

The oldest known lahar event on the mountain is known as the Osceola Lahar, which traveled down the White River through Enumclaw, Buckley, Bonney Lake, Sumner and Auburn about 5,600 years ago.

Osceola deposits cover a total area of around 212 square miles, and it was this lahar that made the Plateau area flat and soil-rich.

The latest large lahar was the Electron Lahar, which traveled down the Puyallup River through Orting, Sumner and Puyallup areas in the early 1,500s.

It flowed roughly 60 miles down to the Puget Sound lowlands into the Electron community, where it was still 98 feet deep.

One of the big differences between the Osceola Lahar and the Electron Lahar is the Electron Lahar was most likely not caused by Mount Rainier erupting.

“There is no evidence of eruption that set it off. No evidence of volcanic ash or fresh lava,” Driedger said. “Our only thought is this happened from a giant mudslide.”

According to the USGS, large lahars have reached the Puget Sound lowlands once every 500 to 1,000 years, although small lahars happen more frequently.

“If future lahars happen at rates similar to those of the past, there is roughly a 1-in-10 chance of a lahar reaching the Puget Sound lowland during an average human lifespan,” a USGS volcano safety document reads.

But Driedger said it’s tough to predict when the next eruption could be.

“Volcanos are not on a time table. Eruptions don’t happen like clockwork,” she said.

Driedger added that it’s unlikely that an Osceola-sized lahar could happen again, because that lahar took out all of the hydrothermically weakened rock on the east side of the volcano.

And even if another lahar did come down on the east side of the mountain, the Mud Mountain Dam would act as a shield for the Greenwater, Enumclaw and Buckley communities.

However, she said there is still a good amount of hydrothermically weakened rock still on the west side of the mountain, making the Puyallup River the most likely direction of the next large lahar, putting the city of Orting right in its path.

UPGRADES TO THE WARNING SYSTEM

According to the USGS, Mount Rainier’s lahars can travel as fast as 45-50 miles per hour and were up to 490 feet deep when confined to mountain valleys.

These large lahars puts cities near the mountain in considerable danger; residents of Orting, for example, can have as little as 40 minutes to evacuate the city after the initial warning is sounded.

What’s being upgraded right now, said Pierce County Department of Emergency Management Public Information Officer Sarah Foster, is the mountain’s monitoring equipment.

“This is a long term project to upgrade the tech,” she said, noting that its mostly a software upgrade, but some hardware as well. “This is not anything dramatic. Everything was working fine, it was just time for an upgrade.”

There are five lahar monitoring stations installed on the Puyallup and Carbon rivers, the most likely path a large lahar will take when it comes off the volcano, said Seth Moran, the scientist-in-charge at the Cascades Volcano Observatory. Two of these stations have now been upgraded.

Before these current upgrades, these stations were basically tripwires to alert the observatory of a lahar.

But knowing that a lahar is coming doesn’t help predict how big it is, or how dangerous it may be to nearby communities, Moran said.

The upgrades, he continued, collect seismograph information that updates the observatory in real time. Webcams have also been installed, so scientists can determine how fast and how deep a lahar is.

“This has the potential for having warning a couple of minutes sooner,” Moran said.

The old system is still in place, and will be running parallel with the new upgrades until they’ve been fully tested and verified, he said.

Separate from the lahar warning stations are nine seismic stations and six GPS stations that monitor volcano activity, which could preclude a large lahar.