The following is written by Lindsay Bosslet for Public Health Insider:

On April 4, the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium published the outcome of the Amio-Lido-Placebo Study in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results are another important step forward in the world of cardiac arrest response – and that means any one of us could be affected by them.

To find out more about what this means for our Medic One team (and for the average Joe), we sat down with Dr. Peter Kudenchuk, Professor of Medicine at the University of Washington and Medical Program Director for King County Medic One here at Public Health and lead author of the NEJM article on this subject.

Public Health Insider: What answers were you seeking from this study? What does “Amio-Lido-Placebo” mean?

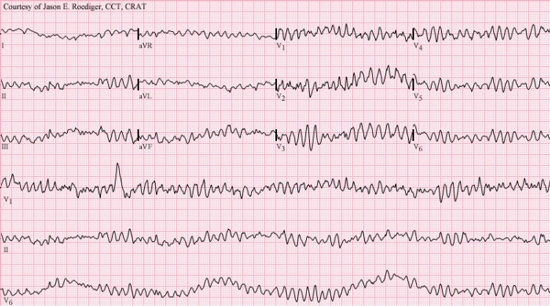

Ultimately, we wanted to figure out the best way to treat cardiac arrest caused by ventricular fibrillation when the rhythm wasn’t responsive to shock treatment. For a very long time, cardiac arrest responders have used a couple of different drugs believed to regulate the heart’s rhythm. But, these drugs (lidocaine and amiodarone), had not been rigorously tested to see which one works better – or if they even work at all.

The study was called the Amiodarone-Lidocaine- or Placebo Study (ALPS for short) because it was a randomized controlled trial comparing both drugs to each other and to a placebo.

PHI: Okay, now we have to know. Which one worked best?

Well, as you might expect, it’s complicated.

In the immediate minutes after paramedics gave the study treatment in the field, there seemed to be different effects from active drugs compared to the placebo. Recipients of either amiodarone or lidocaine, as compared with placebo, required fewer shocks, fewer “hits” of study drug, and less need for ancillary rhythm control medications (like procainamide or magnesium). Active drug recipients were also most likely to be admitted alive to hospital, less likely to re-arrest in hospital and among amiodarone recipients, less likely to require additional rhythm controlling drugs in the hospital. All this speaks to immediate and potentially important antiarrhythmic benefits from these drugs.

PHI: What about the final outcome – getting folks with cardiac arrest out of the hospital and back home?

The primary endpoint of the trial was survival to hospital discharge. There are two ways you can look at this outcome. One is from the perspective of the overall group of patients who were treated, and the types of patients who comprised this overall group.

Two groups of patients were pre-specified by the study as likely to respond differently to treatment: those with a witnessed cardiac arrest and those with an unwitnessed arrest. When it was originally designed, the study predicted that because patients with witnessed cardiac arrest are recognized and treated sooner, they would more likely be responsive to effective treatments than unwitnessed arrests. When first discovered, patients with an unwitnessed arrest are more likely to have already sustained irreversible organ damage resulting from a longer “down time” and less likely to respond to any treatment. This is precisely what was seen in the study – a statistically significant 5% improvement in survival to hospital discharge in witnessed arrests, and no effect from the drugs in unwitnessed arrests.

This suggests that the biggest bang for the buck with antiarrhythmic drugs is when treatment is administered earlier rather than later. Moreover, when these two groups were combined for the overall results of the study, the survival benefit from amiodarone or lidocaine in witnessed arrests was probably muted by the absence of any effect in those with an unwitnessed arrest. Thus the overall outcome in this combined group of witnessed and unwitnessed cardiac arrests was a statistical trend that favored drug treatment (a 3% improvement in absolute survival to discharge) but now fell just short of statistical significance.

In my view, the trial proved that both amiodarone and lidocaine are effective in improving survival. But the reality is while we want everyone with cardiac arrest afforded the chance to be saved, not everyone can or will be saved no matter how effective a treatment might be. This is why it’s so important to not only look at the treatment, but by whom and when it was received.

PHI: Why was finding this answer so important?

Well, for starters, now we have a stronger evidence base for this critical work we do. As you’ve mentioned on this blog, the best place to have a cardiac arrest is in King County. We’re successful because everything we do is thoroughly tested. This study addressed a significant gap in knowledge and practice going back 70 years.

We went into this study knowing that the outcome would either change the game of cardiac arrest treatment or bolster the science behind what we’ve been doing.

PHI: How did the study work?

This large, multi-center study was the first of its kind. In 10 sites around North America (including here in King County), patients experiencing cardiac arrest were entered into the study. Responders delivered up to three syringes of medication – either amiodarone, lidocaine or a placebo of saline solution – and recorded results. The trial was blinded to everyone – meaning the study medication was labeled with a number that was entered into a database, and its identity was only disclosed after the trial was completed.

Because cardiac arrest happens without warning and consent can’t be given ahead of time, patients were unable to give their permission to take part in this study. This required multiple levels of regulatory review and scrutiny of the study to make sure it was conducted with complete safety. For example, an independently appointed Data Safety and Monitoring Board monitored the trial as it was ongoing and had the authority to stop or change how the trial was conducted at any time if any safety issues were seen. No such problems occurred. In addition, the trial required approved by Institutional Review Boards in every community where it was performed.

PHI: What’s next?

I’m proud to be part of a team that values constant evaluation and assessment. We have a long history of research participation, and we continue to strive to improve cardiac arrest outcomes using lessons learned from this and other studies currently being conducted around the world.