Correction: In the print version of this article, published June 24, it was incorrectly reported activist Alicia Busch was from Covington. She lives in Maple Valley.

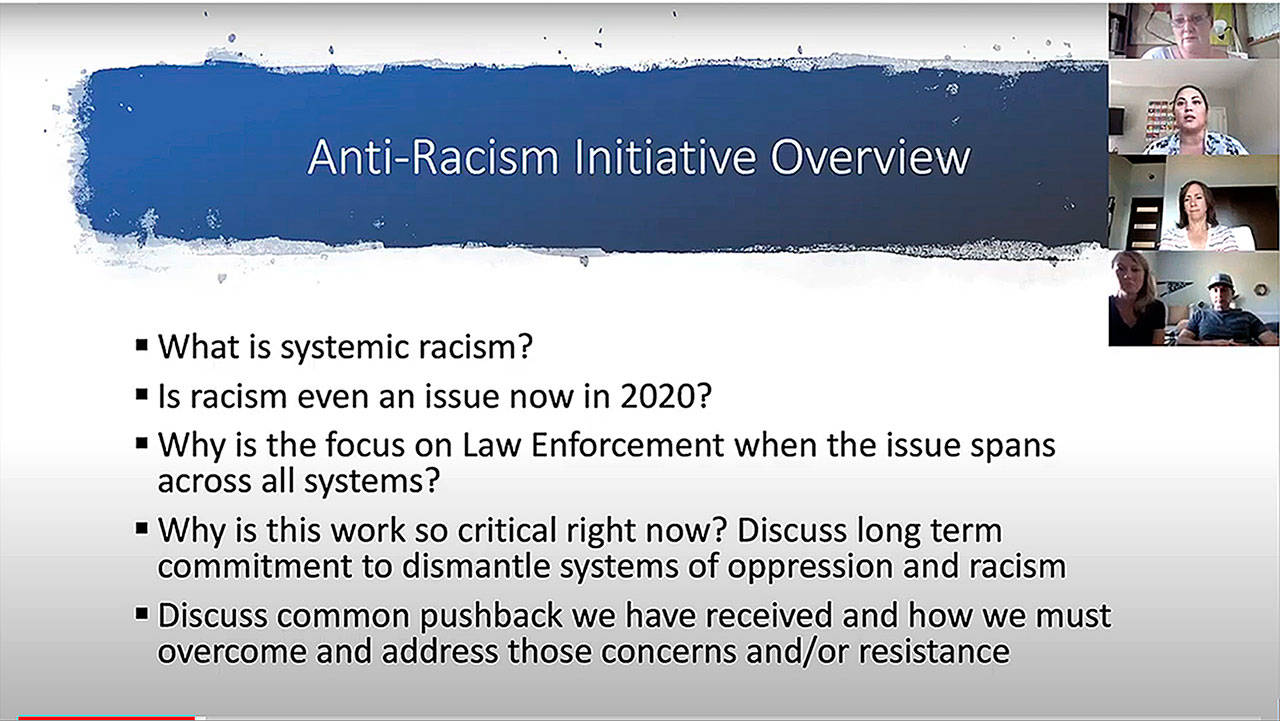

A handful of community leaders and interested residents from four local cities, as well as two of their state legislators, attended an anti-racist and systematic bias presentation and discussion last week.

The presentation, hosted by Enumclaw resident Megan Sheridan and Maple Valley resident Alicia Busch on Thursday, June 18, aimed to be the first stepping stone on a long path to closely examining city and school district systems for racial bias and replacing them with more equitable policies.

Attending the Zoom meeting were Tony Binion and Anthony Wright from the Enumclaw City Council, as well as Enumclaw Middle School Principal Jill Barrett; Erin Stout and Kristiana de Leon of the Black Diamond City Council, as well as Mayor Carol Benson; Linda Olson and Erin Weaver of the Maple Valley City Council, as well as City Manager Laura Philpot and Deputy Mayor Dana Parnello; Jennifer Harjehausen and Jared KouKal of the Covington City Council; Sen. Mona Das of the 47th District; Rep. Lisa Callan of District 5; and a few other community leaders and residents.

The theme of the night was not just how to deal with racism, but systemic racism — ways that a particular system disproportionately affects people of color negatively.

For example, a June 12 Business Insider article shows that between 1967 and 2017, Black workers were paid between 58 percent to nearly 70 percent of what white workers were paid; that the aggregate wealth white households have accumulated between 1989 and 2019 had risen from $20 trillion to $102 trillion, while Black households have made minuscule gains to end up at $6 trillion; that between 2004 and 2018, Black people were denied home loans between two and three times as much as white people; and that while Black people made up 12 percent of the U.S. population in 2018, they also made up a third of the country’s prison population.

“This is literally every system that we interact with, from taxes to education to home loans and home buying, to law enforcement and the judicial system,” said Busch, who co-manages a Maple Valley/Covington-focused Facebook group that promotes intersectional work against inequality. “I am a proud American… I believe in our Constitution. However, we must acknowledge the harm that we have done to what feels like endless groups of people.”

Busch, a Japanese-Jewish woman, has also been heavily involved in pushing back against Patriot Front, a hate group that’s been routinely putting up racist propaganda in South King County cities.

Sheridan, in an interview before the early evening Zoom meeting, stressed that this is not about people as individuals, though she and Busch strongly encourage people to examine their own racial biases.

“You and I didn’t do this. Our parents and grandparents did it. This is from the founding of our country, and we have documents that say the Black community is not equal. We know that,” Sheridan said. “So it’s our time, now, as people, to say those systems don’t work… [and] if we’re unwilling to address that, now we’re accepting racism.”

FIRST STEPS

Given that systemic racism and bias is an all-encompassing issue, it can be hard to know where to start, Sheridan and Busch said.

However, they added, there are three clear steps local cities can take to get the ball rolling.

One is for cities to not only proclaim support for inclusivity, but also strongly denounce hate and establish action items for how the city will improve.

The Enumclaw City Council unanimously approved an inclusion proclamation during its May 21 meeting, followed by the Enumclaw School District in early June. The Black Diamond City Council has also been working on its own proclamation or resolution, though it’s unclear if, or when, it will be presented to the full council.

“We… do hereby proclaim that we reaffirm our community’s shared values of compassion, inclusion, respect, and dignity; and our commitment to building an environment, and a community, in which everyone is valued and everyone has the opportunity to thrive,” the approved Enumclaw proclamation reads in part.

This proclamation did little to impress Sheridan, who, as the mother of a Black teenager, has seen how the world treats her and other white people differently than her child since he was born.

“I feel like an inclusivity statement is a pat on the head for my child… there’s no action. That’s putting out a statement. We’re asking you to take action. We can’t change and make systemic change with a statement. Period,” she said. “So no, it’s not enough. Am I glad you did it? Yes. I am. But to look at my child, who is scared he’s going to be shot walking down the street in Enumclaw, is what he said to me the day before George Floyd was murdered… no, it’s not enough.”

Other actions Sheridan and Busch would like cities to take are to implement anti-bias training and put together a community task force that would examine city policies for racial bias.

Sheridan said it’s not uncommon for white people to say they don’t need anti-bias training and to say they’re not racist.

“That’s what I always said. ‘I’m not racist.’ ‘I have a Black friend.’ ‘I have a Black kid.’ I have a — blah blah blah. Do we still all have racist tendencies and biases? Absolutely. That’s how we were raised… That’s our world. And I have forced myself, in a positive way, to… [see] the world completely different,” she said. “It makes you realize how much bias you have and don’t even realize it, and the stereotypes that have been perpetuated for years through everything — our books, our history, our TV shows, clothing, every aspect. Even things that we say about those that drive next to us. I’m appalled at the things that I realized are my own biases.”

While city leaders and officials are examining their own internal biases — not just during a one-time, eight-hour session, but a continuing series of presentations and discussions — a citizen task force would be examining city policies for racial bias.

In predominantly white institutions like law enforcement or education, “when subvert, or even overt, acts of injustice occur, it’s up to the person with power and privilege who may not see the harm caused to decide whether or not the complainant’s experience is valid or not,” Busch said during the Zoom presentation. “That’s really harmful. To experience an act of racism and be told, ‘That’s not racism,’ is another form of abuse. We need independent and diverse sources of accountability.”

Sheridan put it more plainly: “You and I can’t look at systems and go, ‘That’s going to set up a Black community person… to fail,’ because we don’t know what that is. We’ve never experienced it,” she said, adding that it may be difficult to put a community commission together at first, and if that’s the case, cities should hire groups that can start that work. “There’s going to have to be some budget given — [and] if we start to say that money is an issue over equity, we’ve got a really big problem.”

As for where to start, Sheridan said she has an idea.

“This is a phrase that drives me crazy…: ‘It’s how we’ve always done it,’” she continued. “If that’s our response, it’s probably where we need to start looking, from building codes to businesses to our schools to everything else.”

IMPETUS AND PUSHBACK

Sheridan has known since she was pregnant with her son Hudson that life was going to be more difficult for him than if she had a white child. She said his life has been filled with varying levels of racism, from being told by a preschool teacher that he wasn’t allowed to use a white crayon to color in a person because it wasn’t his skin color to encountering graffiti of a Black man getting lynched in the boys’ locker room in the Tahoma School District.

But it was a more recent incident that set Sheridan on the path to educating other white people about systemic racism.

Details are sparse, given that all the involved parties are minors. But according to Sheridan, a schoolmate of Hudson threatened to “post up” (or fight) her son and call the cops on him “because he is Black,” she said.

Hudson told his mother of the situation and that he “[thought] he’s going to get shot walking down the street in Enumclaw” nearly two weeks after the threats were made — and the day before George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis, rocking the nation.

She called Floyd a hero, not only because his death has sparked protests and calls for change around the country, but also because he “lit a fire under my [expletive].”

“I am embarrassed to say that. How many more Black men did I have to see die? It may have continued,” Sheridan said, tearing up. “But between the combination of what happened with Hudson and… literally being able to picture him instead of George Floyd, is what I needed to see.”

That’s when Sheridan began calling local leaders and community members, specifically people who either know Hudson or “have either said we need to make a change, they have from the dais actively asked for it on the agenda or denounced hate… or are wanting to do things,” she said.

Not all the responses she received were positive, Sheridan said.

During the Zoom meeting, Sheridan referred to an unnamed council member whom she felt was trying to intimidate her into not organizing the meeting by threatening her son.

“I did have one council member from one of your cities telling me that doing this work is going to make Hudson’s life extremely difficult,” she said. “I’m incredibly saddened that we have someone in leadership that thinks threatening a 14-year-old is in any way acceptable. It will not, and should not, be tolerated at any level.”

In the interview prior to the presentation, however, Sheridan identified the elected official as Black Diamond Councilman Patrick Nelson, adding that she didn’t mention his name during the meeting because she didn’t want to distract from the overall message she and Busch wanted to get across.

When asked about the conversation, Nelson said his words were taken out of context, and that he was referring to Sheridan’s plan to confront her son’s bully and how that could backfire for Hudson.

“You want to be careful, because when parents run in to defend [a kid] from [a bully], the bullying doubles,” Nelson said. “This is my experience… that’s all I said. I wasn’t threatening her.”

Nelson added that he’s known the Sheridans for years and considers Hudson a friend.

“My whole point to her was that I agree with what you’re doing. Just be sensitive on how you do it and not add fuel to a fire to make things worse for what you’re trying to do,” he said.

In response, Sheridan said that she stands behind how she received Nelson’s statement, and that the conversation was far more focused on her upcoming presentation, and not the bullying incident with her son.