After its statewide rollout last week, ShakeAlert can now warn Washington residents when an earthquake is about to hit their area.

This early warning system could be especially valuable to Plateau residents, where Mount Rainier can turn from a majestic backdrop into a machine of destruction and death in the matter of minutes, caused by (or causing) an earthquake.

The ShakeAlert system, operated by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network, does not predict when earthquakes are about to hit. Instead, the system quickly detects earthquakes already in progress, including an estimate of the earthquake’s size and location, and delivers alerts to cellphones.

According to the Washington Military Department, this can give regular people seconds of advanced notice of a quake — enough time to “drop, cover, and hold on” to protect themselves.

“Since the majority of earthquake-related injuries are caused by people getting hit by falling objects or falling down while moving during the shaking, seconds of warning will let people take protective action before shaking begins, reducing the chance of injuries,” the department wrote in a press release. “The system also has the potential to automatically close water valves to protect water supplies, lift fire station doors so first responders can get vehicles and equipment out, slow down trains so they don’t derail and even warn hospitals to halt surgeries, among many other capabilities. Dozens of pilot projects in Washington are already testing this technology to reduce earthquake damage.”

Many cellphone users may not have to change their phone settings in order to get Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEAs), although it’s recommended users double check their phone settings to make sure they’re able to receive these alerts. A “how-to” for Android, iPhone, and other cellphone users is included at the end of this article.

MOUNT RAINIER AND EARTHQUAKES

Earthquakes happen all the time around Washington and the west coast in general, said Pacific Northwest Seismic Director Harold Tobin — we just don’t feel them.

Mount Rainier is no exception. In fact, it appears to be one of, if not the most, earthquake-prone volcanoes in the PNSN network, which extends from Washington down to California.

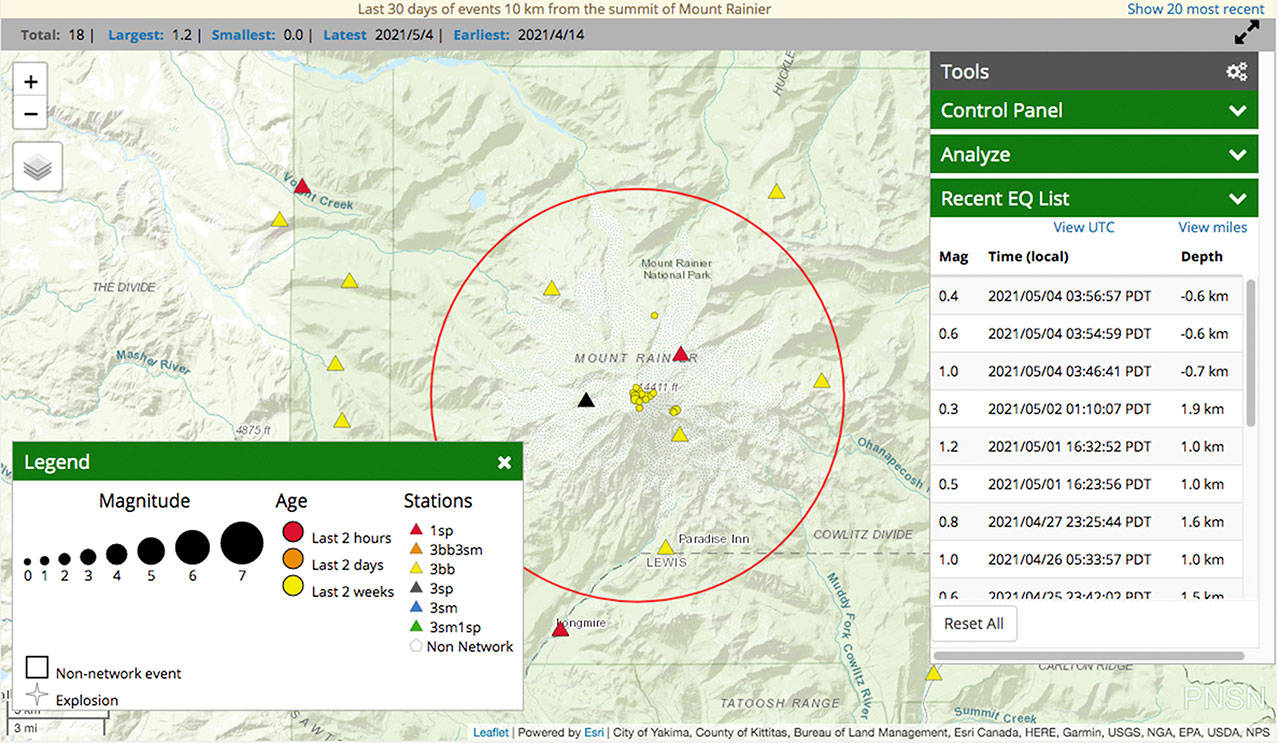

For example, the volcano experienced 22 earthquakes in the last 30 days as of May 5, the largest reading a 1.2 on the magnitude scale, according to pnsn.org. The U.S. Geological Survey says “a few hundred” earthquakes are detected every year near Rainier, “more than any other Cascades Arc volcano except Mount St. Helens.”

These tiny quakes won’t tip ShakeAlert to send out an alert to Enumclaw residents, or to anyone else living in the shadow of the mountain, Tobin said; the threshold for an alert ranges from a magnitude 4.5 or 5.0, depending on the phone that receives earthquake alerts.

In fact, most of Rainier’s earthquakes will likely not register with ShakeAlert, given that the largest recorded earthquake beneath the volcano was only a magnitude 3.9 in 1973, with similar earthquakes reported in ‘76, ‘90, 2002, and 2004.

But none of those quakes coincided with an eruption or other major volcanic event like a lahar, both of which can be triggered by — or cause — an earthquake large enough to send out an notice through ShakeAlert.

“You could speculate that a big eruption further back in the past might have caused a significant earthquake,” Tobin said. “The only analogy I say we have is what happened to Mount St. Helens.”

According to the USGS, the May 18, 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption was preceded by a magnitude-5+ quake — one of the many signs that the volcano was about to blow.

However, Tobin stressed that not every eruption, or even most eruptions, are foreshadowed by a large quake.

“A lot of volcanic eruptions don’t produce a sizable [earthquake],” he continued. “They erupt without any earthquakes large enough for the ShakeAlert system.”

WHAT ABOUT ‘THE BIG ONE’?

If you’ve lived in western Washington for a while, you’ve probably heard of “The Big One” — an earthquake that some experts believe will level the west coast.

“Our operating assumption is that everything west of Interstate 5 will be toast,” Kenneth Murphy said in a 2015 New Yorker article about the supposed earthquake; Murphy is the director of FEMA’s Region X, which covers Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Alaska.

While the New Yorker article garnered some criticism about how it framed “The Big One,” experts generally agree on a few things, like that this future earthquake would originate in what’s known as the Cascadia subduction zone off the west coast of the U.S.

PNSN and other organizations call this a “megathrust” fault line, owing to the fact it’s capable of producing magnitude-9 earthquakes. Japan suffered such an earthquake in 2011; it triggered a 130-foot tsunami, directly caused a meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, killed nearly 20,000 people, and cost an estimated $235 billion in damage, according to the World Bank.

But how would such an earthquake affect Mount Rainier?

“There is some evidence of at least time association between some very, very large earthquakes — the very few in the world that have happened at the magnitude 9 scale — being associated in time with eruptions of nearby volcanoes,” Tobin said, pointing to the megathrust Valdivia earthquake in Chile on May 22, 1960.

Also known as the Great Chilean earthquake, it was the most powerful earthquake ever reported since scientists started recording earthquake magnitudes. It’s widely believed to have caused the Cordón Caulle volcano to erupt, sending up an 8 km,or 5-mile high, ash column.

(For comparison, Mount St. Helen’s ash column was 19 km, or 12 miles high.)

“However — and there’s a lot of howevers — … many, many more of the large earthquakes on the planet have not been associated with eruptions. And I would say that out best scientific understanding of volcanoes work is that you still need a volcano to be primed and ready to go, and maybe an earthquake could be the trigger that pushes it over the edge,” Tobin continued. “While it’s not inconceivable that an eruption of one of the Cascade volcanoes like Mount Rainier could be triggered by a large earthquake, it is also a pretty remote possibility, and much more unlikely than likely, I’d say.”

HOW TO GET SHAKEALERT

Android phones:

- First, use the search function in “Settings” to find “Emergency Alerts” or “Public safety messages.” You may have to click the three dots in the upper right-hand corner of the screen, click settings and click alert types.

- If you can’t find “Emergency Alerts” by searching in “Settings,” try searching for “Emergency Alerts” in the text message app instead. You may have to click the three dots in the upper right-hand corner of the screen, click settings and click alert types.

Apple phones:

- Tap “Settings” > “Notifications”

- Scroll to the bottom of the screen.

- Under “Government Alerts” tap “Emergency Alerts” and “Public Safety Alerts” to turn them on or off.

Other phones:

- To check if Wireless Emergency Alerts are turned on for other phone types, contact your mobile phone carrier and/or mobile phone’s manufacture’s website for additional information. If you already get AMBER Alerts, you may get these alerts, too. But it’s not guaranteed because phones use different settings. Ask about emergency alerts or public safety alerts.