In recent years, the Regional Affordable Housing Task Force estimated that King County would need a collective 244,000 more units of housing by the year 2040, not only to keep up with the quickly growing populations of many different cities, but also to assure that affordable options were available for low-income families.

Housing advocate and market expert Peter Orser said cities like Bellevue, which have seen enormous economic and population growth, are only making “small advancements” toward that goal. He said the city of Bellevue, for example, built a little more than 300 new units of housing during 2020.

“We’re not keeping up with our economic success,” Orser said.

Now as cities individually recognize the need for increased housing capacity, they are trying to incentivize property owners to invest in Accessory Dwelling Units.

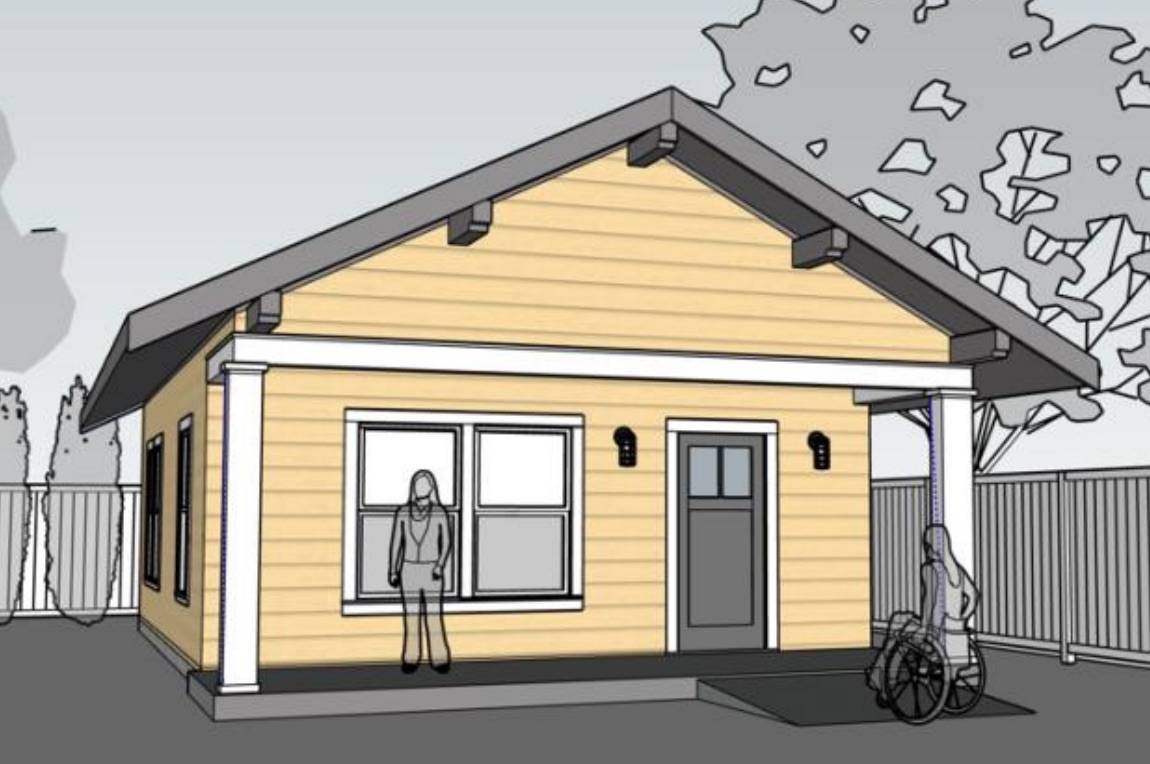

ADU is a fancy word for a backyard cottage or a “mother in law quarters,” so to speak. A detached home, while small, can provide basically all the same amenities as a normal house.

Orser said ADUs are advantageous for cities because they are a “sensitive” way to expand a neighborhood’s housing volume and density without having to rezone. He said they also allow for homeowners to have more security and control with their property.

However, cities are handling the incentivization of ADUs in different ways across the county. Different cities have different building codes and requirements that in some cases may hinder the building process or even the purpose of building one.

Orser mentioned some municipalities like Auburn require at least one space of off-street parking per ADU — something that is presumably intended to mitigate street usage, but also may be unfeasible for certain properties.

He said other cities currently prohibit ADUs from being rented out to tenants, likely defeating the economic incentive to invest for many.

The non-profit research organization Sightline Institute said 89 cities in the state also require that the property owner continues to live somewhere on the property, either in the original house or in the ADU.

Sightline Institute identified this requirement along with the requirement for off-street parking spaces as the two largest barriers to the adoption of ADUs.

In recent years, Seattle changed its policies to allow multiple ADUs on a property, striking the owner-occupation requirement and parking space quota as well as allowing short-term rentals of the units. The city also eased the regulatory burden of building ADUs by shortening the waiting periods to build them.

Sightline Institute called Seattle’s policy the best in the country for ADUs and compared the roughly 500 ADU permit applications filed in Seattle during 2020 to the only 71 filed in Bellevue — despite being a city that is desperate for more housing with thousands of more jobs in town than available housing units. Bellevue maintains some of the most burdensome ADU requirements in the region, according to the Sightline Institute.

They claim that Bellevue’s requirements for ADUs to be attached to the original home, parking space quotas, banning of renters and a three-year waiting period all create difficult conditions for property owners to develop needed housing units.

Orser said part of King County’s housing problem is not only the volume of housing, but also the lack of diverse housing options. He said increasing the variety of housing options will also help the general affordability of the market, and that ADUs could be a part of that solution.

Coalition For More Housing Choices spokesperson Aaron Pickus said ADUs not only offer expanded housing capacity, but they are also conducive for different kinds of families and living situations.

For example, as family members age past the point of self-reliance, ADUs can allow for them to live closer to their family instead of moving to a long-term care facility. Or, a group living situation in a main house could have a needed caretaker living in the backyard cottage.