For endangered salmon in the Green River, a century-long homecoming may soon be at hand.

The Howard Hanson Dam recently received an injection of $220 million in federal funding to design a fish passage project that would nearly double the spawning ground for several threatened fish species in the Green River, U.S. Senator Patty Murray announced this month.

“This funding will go a long way in our fight to save the salmon, opening up miles of critical habitat,” Sen. Murray said in a press release. “This is a big victory for the Muckleshoot Tribe, our salmon and orca, the entire Puget Sound, and all of Washington state.”

The money, secured from 2021’s $1.2 trillion federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, could be the financial boost the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers needs to finally open the river’s upper watershed, mostly untouched by both fish and humans for the last century, back up for spawning and migration.

“It’s huge,” said Katherine LaPonte, a civil works project manager at the Corps of Engineers. “This funding is very significant, because it fully funds the entire design and beyond. … It’s really kind of crazy that it’s actually going to happen.”

Between the Howard Hanson Dam and its terminus at Seattle’s Elliot Bay lies dozens of miles of Green River habitat used for spawning by steelhead and salmon. However, urbanization and climate change will likely continue to chip away at the quality of this chunk of the river, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

But locked behind the Howard Hanson lies more than 100 more miles of high-quality spawning and rearing habitat for fish in the river’s watershed, according to the NOAA. Opening that upper watershed above that dam to fish would be a game-changer for the threatened Puget Sound Chinook salmon and steelhead, scientists at NOAA said. And the fate of those fish is intertwined with the endangered Southern resident killer whales, or Orcas, which feed on the fish.

“It just seems so amazing,” Army Corps fish biologist and environmental coordinator Nancy Gleason said in an interview. “If we could do that, it would really restore a resilient Chinook salmon population in the Green River, and clearly have huge benefits for the southern resident killer whales’ diet in the Puget Sound.”

A WHOLE NEW WORLD

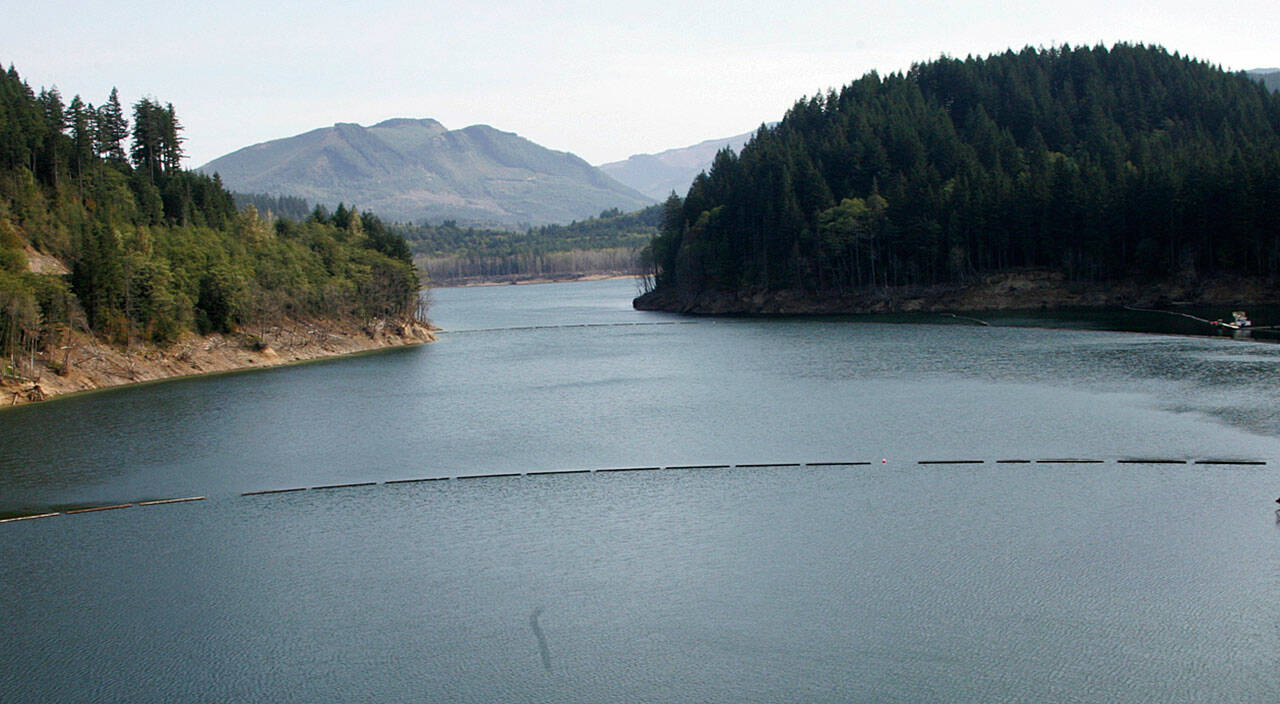

Located about ten miles east of Black Diamond, the Howard Hanson Dam holds back the Green River from flooding over the Green River Valley. In doing so, the dam also manages and improves the river’s strength in the drier part of the year via the water banked in its reservoir.

Guided by instinct and a carefully-tuned sense of smell, salmon and steelhead in the Pacific Ocean return to these waters each year to spawn in relative safety. Their young swim back to the sea to live out most of their lives.

But as anyone who’s attended a Pacific Northwest salmon grill can attest to, the fish are always in high demand.

“There’s a lot of survival points in the salmon life cycle,” Gleason said. “We lose a ton of fish all through the river to lots of predators, like the cutthroat trout or great blue herons. Pretty much everything in the environment loves to eat salmon.”

The upper watershed is closed to human development since the Tacoma Headworks Diversion Dam uses the river for drinking water, so the area would be prime real estate for spawning fish.

“I don’t want to call it ‘pristine’ habitat, but it’s undeveloped,” Gleason said. “There’s active timber harvest in the watershed, but there’s not much other activity up there because it’s closed for drinking water supply. … It is amazing habitat, and should be highly productive.”

The watershed is “extremely valuable” to all the fish that could use it, but especially the steelhead and Coho salmon, which travel further upriver than their Chinook and Chum cousins, Gleason said.

The fish have no way of accessing this upper watershed – yet.

Getting there is a two-dam affair, since the Diversion Dam, owned by Tacoma Public Utilities, lies about three miles downstream of Howard Hanson. It was built in 1912, and ever since then that watershed has been locked out for the fish.

Howard Hanson was finished in 1962, and while its reservoirs allow officials to moderate river flow in the summer and boost fish spawning below the Headworks dam, both dams are obstacles to the upper watershed.

Tacoma Public Utilities has already built a fish trap-and-haul system at Headworks to bring the fish up past both dams, and they have the facilities to get fish back down the Headworks dam.

But getting the juvenile spawn back down from the Howard Hanson Dam presents an engineering challenge: The dam’s water level fluctuates by more than 100 feet depending on the season and weather. A tunnel at the bottom of the dam theoretically allows passage, but salmon like to swim near the top of the water, and diving that deep to find the passage is “completely unnatural” for them, Gleason said.

When researchers tried bringing salmon up to spawn in the upper watershed, Gleason said, only five percent of the returning fish managed to figure out how to escape the reservoir downstream.

The rest “would just keep swimming around in the reservoir and die without spawning,” Gleason said. “They never found their way out into the ocean, never fulfilled their purpose in life to get big in the ocean and swim home.”

The NOAA wants the dam to get 75 percent of the juveniles safely through.

So the planned solution is five large openings to the tunnel, stacked one-on-top-the-other, so that the fish always have an entry point no matter where the surface of the water sits. That’s what engineers hope to have completed by 2030.

THE PROJECT

With a growing demand for municipal and industrial water in Tacoma, officials saw value decades ago in adding room for water storage in the Howard Hanson Dam reservoir. The scale of that work also presented an opportunity to finally work out a fish passage solution. Putting it all together has been a collaboration between the Army Corps and biology and engineering experts from fish and wildlife agencies and tribal groups like the Muckleshoot Tribe.

The Howard Hanson project, authorized by congress in 1999, sought to both increase the dam’s water storage to the tune of more than 30,000 acre-feet, which would aid its flood control and water management abilities, and to improve the prospects for fish in the river.

But it was foiled – temporarily – by an underestimation of the project’s cost.

Congress authorized the project in 1999 and construction began in 2003, but the project ground to a halt in 2011 after the projected costs began to exceed congressionally authorizing funding limits.

“Folks went, ‘Oh gosh, this is going to be more expensive than we’re allowed – we’re not going to be able to get this funding, because it exceeds the cost limit,’ ” LaPonte said.

In 2019, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ordered the Corps to finally finish the fish passage facility no later than 2030, and to prove that it is actually improving fish survivability and reproduction. A year later, all of Washington state’s congresspeople came together to formally call upon the Army Corps to prioritize salmon passage at the dam.

Now it appears the time to do so has finally come. But the 2011 stoppage is more frustrating than simply hitting the “pause” button.

Because the Corps underestimated the cost of building the facility in the first place, they needed funding to re-analyze and re-validate the project so that this time it gets done on time and on budget. They got that funding in 2020.

“You have to get money to figure out how much money you actually need,” LaPonte said with a laugh. “That’s what happened in 2020. … It’s been a long time sitting on the shelf.”

Now funded to finish designing the project itself, the Corps estimates construction will start by 2026 if all goes according to plan, LaPonte said.

While the new boost of $220 million will at the very least fully fund the design of the project, the Corps expects they’ll need more funding to actually finish building the fish passage facility, LaPonte said.

While they’re still determining the specifics, LaPonte said the costs to finish the project even after the grant will be in the “hundreds of millions.” That’s partly due to how early they are in the design stage, she said, and the costs might be lower in the ultimate design.

“These are incredibly complex facilities that take a long time to design and a long time to build,” LaPonte said. “And we want to do it right.”

The good news is that much of the water storage work is already done, LaPonte said. Once the fish passage facility is done the Corps plans to add even more water storage to the dam.

If all goes to plan this time, the Corps will have a design done in three and a half years, and only another four years of construction to do after that.

“The goal is to not have any real break in effort,” LaPonte said. “If we’re not waiting on funding to trickle in, then we can really lock in our schedules and drive the team to stick to it.”

Editor’s note: The print version of this story misspelled Nancy Gleason’s name. We regret the error.