For genealogists, one of the most powerful tools outside of preserved family documents is the official United States Census, which attempts to track information on every United States resident for the purpose of congressional districting. But the census’s usefulness in this secondary purpose is tempered by a limitation imposed to support its primary objective: to preserve citizens’ privacy, the names and addresses of respondents are kept confidential for 72 years.

So in the second year of each decade, dedicated family tree trackers eagerly anticipate the release of another census from more than two generations past.

On April 2, the United States Census Bureau released the raw data of it 1940 census, divided into thousands of enumeration districts, themselves made up of dozens to more than a hundred pages of names. It’s no exaggeration to say finding an ancestor among such a volume of information is like seeking a needle in a haystack for the amateur.

Heritage Quest Research Library is one nonprofit organization that assists and guides the search.

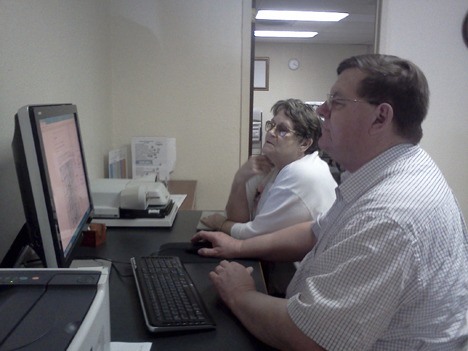

On Friday, Library Director Jim Johnson was helping Caroline Harkness find a family household in what is now the SeaTac area. The search is a challenge: in 1940, the area was not an airport-supported city, but a swath of unincorporated King County that makes tracking the specific enumeration district a headache. Johnson accidentally begins the search in Seattle and has to find his way southward as he clicks through disconnected blocks of map.

“Well, here we go, here’s the rest of King County,” he said.

“Ah!” Harkness said. “Zenith. That’s something I know. Go right.”

Johnson does.

“Let’s see: there’s Kent, there’s Des Moines…” Harkness said.

“I don’t see EDS numbers anymore,” Johnson said.

“There’s Kent, there’s Meeker,” Harkness said as she squinted at the computer screen. “Right there. There’s 188th, and we lived on 182nd.”

As they zeroed in on the specific part of map on which Harkness resided, they had to switch websites twice: first to Ancestry, then to a service called Steve Morse.

The search takes an hour of solid work, but the two were finally rewarded with a set of Harkness’s relatives’ names on a spreadsheet.

This type of hunting and scratching is just the nature of Census genealogy in the first months of release, Johnson said. The search has become simpler in the age of the internet, but in coming months more states will have their data indexed by third party services. When that happens, respondents will be able to be found by name.

Every 1940 Census respondent was subject to 33 questions ranging from birthday to race to household income, and 5 percent of respondents were subject to 18 bonus questions, including the birthplace of a person’s parents, what language was spoken in the home in early childhood, whether the respondent took Old-Age Insurance or Railroad Retirement payroll deductions in 1939 and how many marriages and children women in the household had.

Some of the bonus questions border on the invasive, but in genealogical terms, they’re like winning the lottery, Johnson said.

“If you’re lucky enough to have a relative that fell on line 14 or 29 of the Census taker’s form, you have so much more information with which to track down relatives,” he said.