As Washington state legislators reconvene for a short session, money earmarked for a civil lawsuit against a local group home for sex offenders has been gathering dust.

According to Save Our Children Enumclaw, a grassroots-turned-nonprofit organization that has led the fight against Garden House, a Enumclaw-area “less restrictive alternative” (LRA) home for former residents of the McNeil Island Special Commitment Center for sexual predators, the group is waiting to see which, if any, of the three bills introduced in the state House of Representatives regarding sex offenders get any play before potentially filing a civil suit.

An LRA is a transitional home for sex offenders after they’ve been cleared to leave the commitment center by McNeil Island experts. Security often includes wearing a GPS ankle bracelet, sticking to pre-approved routes when they leave the LRA, and checking in with their transition team about when they arrive and leave outside locations, but more safety measures can be put in place, depending on the individual.

After news about Garden House taking in resident Stevan Knapp last winter started an uproar among the local community, as well as county and state lawmakers, early last year, Save Our Children raised about $60,000 in order to file a civil suit against the LRA to get it to evict resident and shut down the LRA.

What the suit might allege is unclear, though multiple issues, from potential improper zoning or permitting at Garden House to security lapses and oversights, have been brought up in past conversations.

But before a suit could be filed, Knapp was removed from Garden House after a judge ruled last August that living in the LRA was no longer beneficial to his mental and physical safety, citing numerous potential security threats.

And then in September, Garden House’s operators, Rich Minnich and Jill Rockwell, terminated their contract with the state Department of Social and Health Services, said department Media Relations Manager Tyler Hemstreet.

This news was previously unreported, though Save Our Children announced over Facebook that Minnich and Rockwell took residence in the home last December.

With no Garden House left to sue, Save Out Children Enumclaw President Cathy Dahlquist said the money remains in a bank account overseen by the nonprofit’s Board of Directors.

“We’re in a holding pattern,” Dahlquist said in a Dec. 27 phone interview, adding that the group is waiting to see what Minnich and the DSHS do next, or what bills are passed by the state legislature, before possibly moving forward.

STATE BILLS

There are three bills that were introduced in the state house — House Bills 1926, 2093, and 2096. All three are sponsored by local Reps. Eric Robertson and Drew Stokesbary, as well as other lawmakers.

HB 2093 is the meatiest and would make multiple changes to RCW 71.09, which dictates many of the laws around how McNeil Island residents are transitioned into an LRA and how the community is alerted to the move.

Perhaps the biggest change is redefining the “fair share principle,” which stipulates that counties need to be able to house the equivalent number of sex offenders at McNeil Island that committed a crime in that county. For example, if King County had 10 sex offenders committed to the island, they would need 10 LRAs, or some equivalent.

HB 2093 changes “county” to “region,” though the definition of “region” is unclear in the bill.

Another potentially meaningful change is adding to the list of places where LRAs can be sited. Currently, McNeil Island residents moving to an LRA are generally sited to places away from “risk potential facilities” or “activities” like schools, day cares, public parks, playgrounds, places of worship, and others, though this can be on a case-by-case basis.

HB 2093 adds to the bill that no McNeil Island resident can be housed adjacent to, across the street from, or within the line of sight of risk potential facilities/activities. The bill also adds “locations where the public is known to congregate,” to the list of risk potentials, which could majorly limit the places where LRAs can operate.

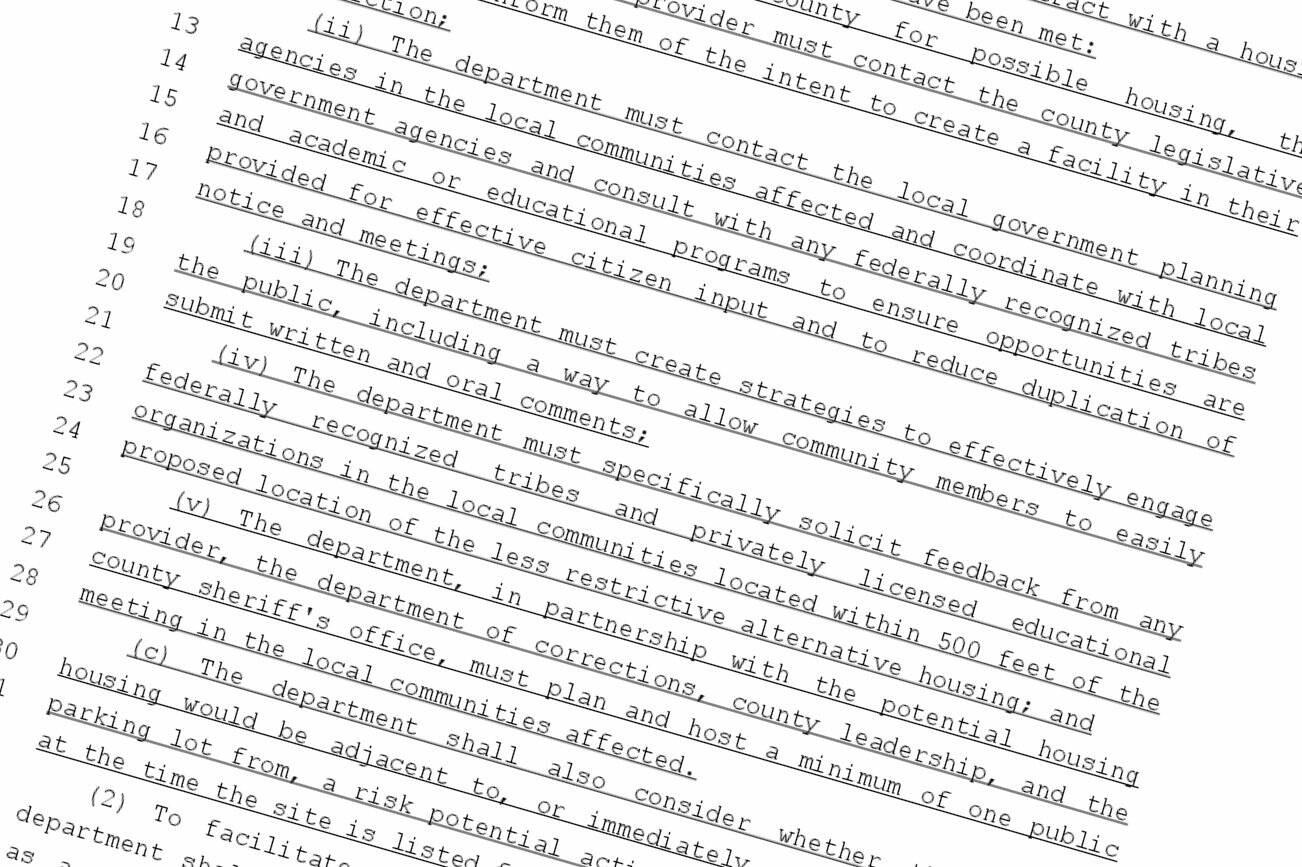

Finally, HB adds additional language that would require the state Department of Social and Health Services to alert numerous lawmakers and agencies before entering into a contract with another agency to operate an LRA.

Currently, the DSHS is not required to alert anyone that the department signed a contract with an LRA operator.

Under the proposed change, the DSHS must alert the local county council, government planning agencies, tribes, school districts, as well as coordinate with those agencies on how to communicate with the public, and at least one public meeting must be held.

Finally, a new sections added by the bill include requiring DSHS to make recommendations on switching from a county fair share principle to a regional fair share principle and review the availability of public services for sex offenders in each region, including the availability of chaperones, sex offender treatment options, personal care or in-home assistance by August 2025.

HB 2096 is a shorter version of HB 2093, and only amends RCW 71.09 to require the DSHS to alert local government entities and host a public meeting.

Finally, HB 1926, if passed, would exempt those who are under RCW 71.09 supervision from receiving “supervision compliance credits,” which takes time off an offenders’ supervision sentence for making progress in their supervision goals like participating in interventions, treatment, etc.