A Buckley man is suing Pierce County deputies for allegedly using excessive force in his 2020 arrest, claiming the “seven-minute assault” has permanently damaged his body and left him with “intense” psychological injury.

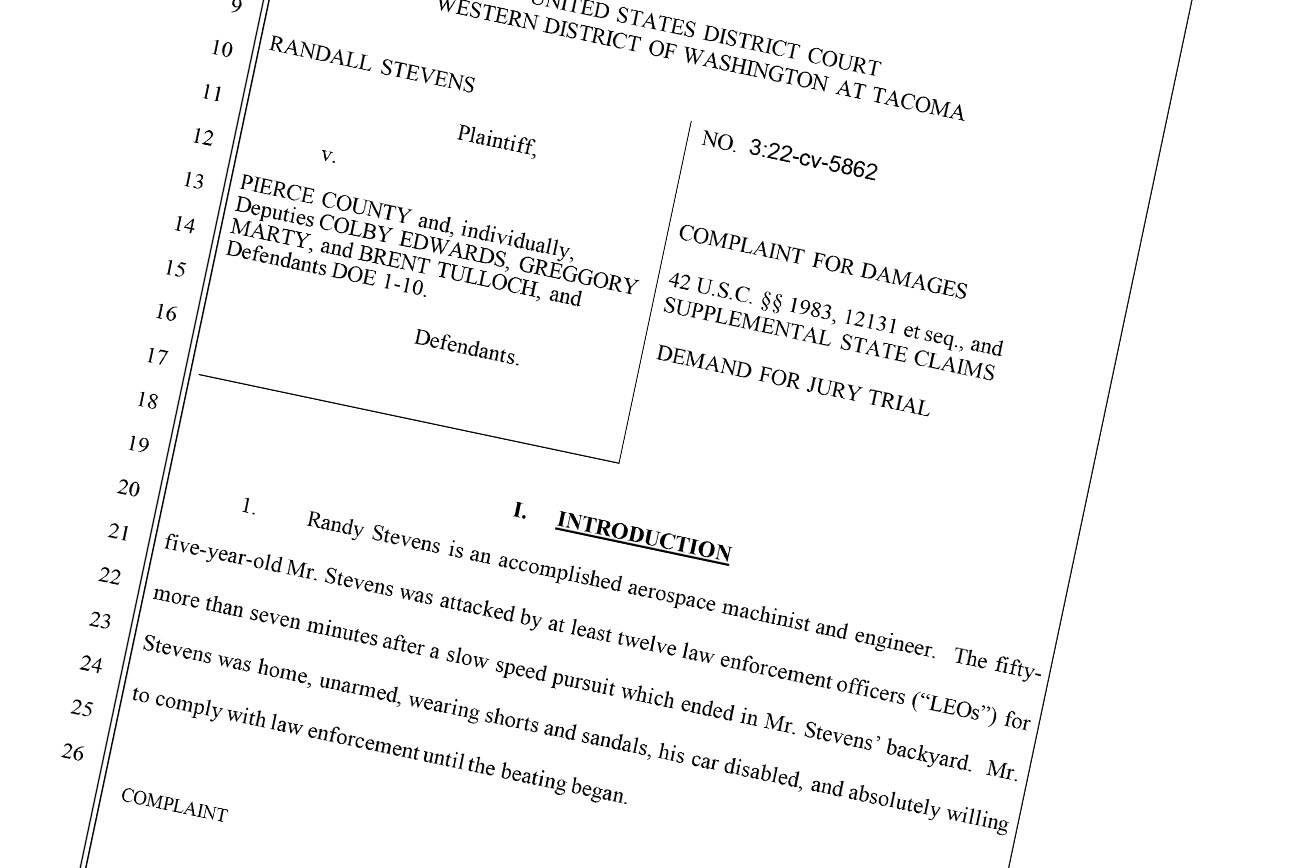

Randall Stevens filed the lawsuit in the federal Western District of Washington court in Tacoma on Nov. 10, naming three deputies involved in the incident and alleging 10 more unnamed defendants, plus the county.

The lawsuit describes a vastly different point-of-view of his arrest than what court papers of his arrest paint — read on for Stevens’ account.

According to the 2020 probable cause statement from Stevens’ arrest, deputies saw him speeding down 258th Avenue E. at about 80 mph, more than three times the limit. Deputies chased after Stevens, who sped up as he turned onto 96th St. E heading toward Mundy Loss Rd. E. Stevens then ran a stop sign and stuck some rocks or other landscaping debris, which deputies said prevented him from speeding into a nearby home.

Deputies, thinking the car could no longer run, exited their vehicles, but Stevens backed up into a patrol car and took off on Mundy Loss Rd. E, toward state Route 410. More deputies attempted a couple of PIT maneuvers to being Stevens to a stop, but failed.

Stevens stopped again, this time at the intersection of 250th Avenue E and 112th St. E, but when deputies again attempted to contact him, Stevens backed up into the patrol vehicle for a second time and drove away behind the back of a nearby home into a field; deputies learned later this was Stevens’ property.

The vehicle truly disabled, deputies approached Stevens at gunpoint, finding him to be “extremely uncooperative” and refusing to listen to orders. Deputies attempted to remove Stevens from his car, and after a short scuffle, tased him, but Stevens continued to resist officers from inside his vehicle.

At this time, more deputies and Bonney Lake police officers arrived on scene; one used a form of pepper spray while others made “moderate-force strikes” on Stevens hands to get him to let go of the steering wheel and force Stevens out of the car.

The struggle continued on the ground as Stevens continued to resist arrest, and even managed to “perform a push up with multiple officers attempting to hold the defendant down” to regain control of his arms. At the same time, Stevens was telling officers that he couldn’t breathe, but when officers told him to stop resisting, refused to do so.

During the fight, one officer “delivered three flashlight strikes to teh (sic) defendant’s right side/rib area” and “‘jabbed’ his right palm against the defendant’s locked elbow several times”; another deputy “used several strikes to the defendant’s upper left ankle… with his flashlight”.

Finally handcuffed and put into a “recovery position”, Stevens said he didn’t know why officers were there and said he didn’t do anything wrong.

One deputy looked into Stevens car and found a beer bottle on the floor of the driver’s side of the car, and three beer cans behind the from passenger seat; the car reportedly “reeked of the smell of intoxicating beverage”.

Stevens was officially charged with two counts of second-degree assault, attempting to elude officers, DUI, attempted disarming of an officer, and resisting arrest.

He originally pled not guilty, but later changed his plea and was convicted of attempted third-degree assault, reckless driving, damage to attended vehicle, and obstructing law enforcement in October 2021. He was sentenced to 328 days incarceration, but the sentence was suspended when a $500 fine was paid.

THE LAWSUIT

Events laid out on Stevens’ lawsuit conflict with police account of the arrest; while deputies described him as actively (or statically) resisting arrest, which included trying to take control of a deputy’s taser, statically resisting law enforcement’s attempts to control his limbs, and kicking an officer, Stevens claims he was “frozen with fear” due to having recently watched footage of George Floyd being murdered by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin and law enforcement’s increasingly-escalating behavior.

“At no time did any officer attempt to deescalate the situation, and at no time did Mr. Stevens actively resist,” the complaint reads.

It should be noted that Stevens’ complaint does not recap how he and law enforcement ended up in said field. However, Stevens points out that his toxicology report from the incident came back clean, though did not deny or refute that alcohol was found in his vehicle.

According to Stevens, his first direct contact with officers involved a Pierce County deputy and Buckley police officer pointing their guns at his head and “screaming ‘get the f*ck out of the car!’” and other “confusing commands”.

Stevens alleges it was only 23 seconds after first contact that law enforcement deemed him “uncooperative”, and another 16 seconds before a deputy radioed out that he was “fighting” with law enforcement.

“The ‘fighting’ thus far consisted of the two [law enforcement officers] punching and grabbing one man sitting in a disabled car with his hands on the wheel in his own backyard,” court documents read.

Stevens was then tased, but he managed to pull the wires out of his neck and put his hands back on the wheel, “a feat of confused compliance and self-preservation”, documents continue.

As he was tased a second time, one law enforcement officers allegedly yelled, “oh sh*it, he’s resistant to tasers!”, triggering “an instant escalation of the attack.”

Steven then described being punched in the jaw, having his knuckles smashed with a flashlight, and bearing the brunt of a full can of pepper spray before being forced into the fetal position outside the car — all of which is being labeled as Phase 1 of the attack.

Phase 2, then, was when multiple officers “applied force to nearly every square inch of [his] body as he lay face-down on the ground” while being “kicked and punched from every direction to every part of his body.” This forced Stevens’ right arm to be stuck underneath his body, meaning Stevens could not physically comply with officers’ demands to give them control of the limb.

Phase 3 came five minutes later, and it’s the damage sustained from this point on that Stevens is suing for.

Stevens claims Deputy Colby Edwards decided to tase him in the leg at this time, rather than assisting other officers in gaining control of Steven’s right arm.

He also alleges that Deputy Brent Tulloch, who was controlling Stevens’ legs (Stevens denies being able to kick the deputy, as he was covered by officers), decided to use his 1.7-pound Streamlight flashlight to “smack” Stevens’ ankle until the fibula “fractured twice in a spiral shape”.

Court documents allege that the deputy did not carry the standard-issue ASP 21 steel baton, which weighs just over a pound.

Stevens alleges this use of force is considered “deadly” under Pierce County Sheriff policy.

Stevens further alleges that Deputy Greggory Marty was all the while kicking him in the ribs, and at one point, Stevens’ head.

Finally, Stevens alleges 10 other defendants, unnamed as of now but may be named later during discovery, assisted in injuring him or were indifferent to his injuries while he was “forced” to walk on his broken ankle to the ambulance, failed to note his injuries during intake, and confiscated his crutches and splint and failed to accomodate his injuries while in jail.

Stevens is officially suing these 13 defendants for excessive force, failure to accomodate a disability, negligence, and common law battery; he is requesting a trial by jury and compensation for his past, present, and future suffering.

The Pierce County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, which handles civil suits for the sheriff’s department, said it does not generally comment on pending litigation.