Editor’s note: As of May 14, 2022, attorneys representing the family of Quincy Bishop have not yet filed suit against the City of Buckley in this case. The Courier-Herald will update this notice if and when they do.

A trio of officers, including one from Buckley PD, have been found justified in fatally shooting an armed Carbonado man in Puyallup last year in a recently concluded use-of-force investigation.

The findings, released last month, resolve a year-long review of the 2020 shooting death of 30-year-old Quincy Bishop. But the case is not over for members of Bishop’s family, who plan to sue over a shooting they argue was unnecessary and improper.

Police on Nov. 1, 2020 were investigating allegations that Quincy Bishop assaulted his ex-girlfriend and threatened her and their children earlier that morning in Carbonado. Officers say that while trying to arrest Bishop at his brother’s Puyallup home later that evening, Bishop grabbed a gun in his waistband. Unable to keep Bishop from getting hold of the gun, three officers — Buckley PD’s Arthur Fetter, Puyallup PD’s Barclay Tuell and Pierce County sheriff’s deputy Travis Calderwood — fired at Bishop and killed him.

(This case is unrelated to the recent Jan. 9, 2022 Carbonado homicide investigation, in which the suspect reportedly killed himself after a police chase.)

Under state law, any police use of force that results in great bodily harm or death must be investigated by an outside agency — in this case, Tacoma PD and Pierce County. Their investigation, which focused only on the officer’s use of force, found that the officers’ decision to shoot was “lawful and justified” because they “were faced with a suspect who had (already) committed a serious felony” earlier that day and who could have injured or killed the officers had he gotten control of his firearm.

Quincy Bishop’s brother Cory Bishop, 30, was only feet away when his brother was killed. He disputes much of the police record, argues officers made a series of poor decisions when contacting Quincy, and says his brother didn’t have to die that night.

“(Law enforcement) is a hard job,” Cory Bishop said in an interview. “I get it. I have a lot of other friends who are police officers too. … Fact of the matter, for me, is that this was 100 percent preventable. My brother didn’t need to die. His daughters didn’t need to be orphaned. And a lot of things could have been done differently, and it’s frustrating that none of that is addressed in the police report.”

Jack Connelly, the Tacoma-based civil attorney representing the Bishops, called the impending civil suit against the city “a strong case” and a chance to independently investigate the officer’s actions.

An initial tort claim argues Bishop’s death was “senseless and unnecessary” and accuses the officers of failing to control or deescalate the scene and of unfairly restraining Cory Bishop after the shooting. The claim seeks roughly $40 million in total damages.

Tort claims are requests for compensation due to civil wrongdoing, as opposed to criminal charges. State law requires torts to be filed before lawsuits are filed, which gives the involved parties time to decide whether to settle the tort or go to court. Connelly said that Buckley will be the primary defendant in their legal case, though Puyallup and Pierce County are also in the scope of their lawsuit.

“It was a situation handled poorly, by poorly trained police officers, who didn’t know how to de-escalate or control the situation,” Connelly said in a phone interview.

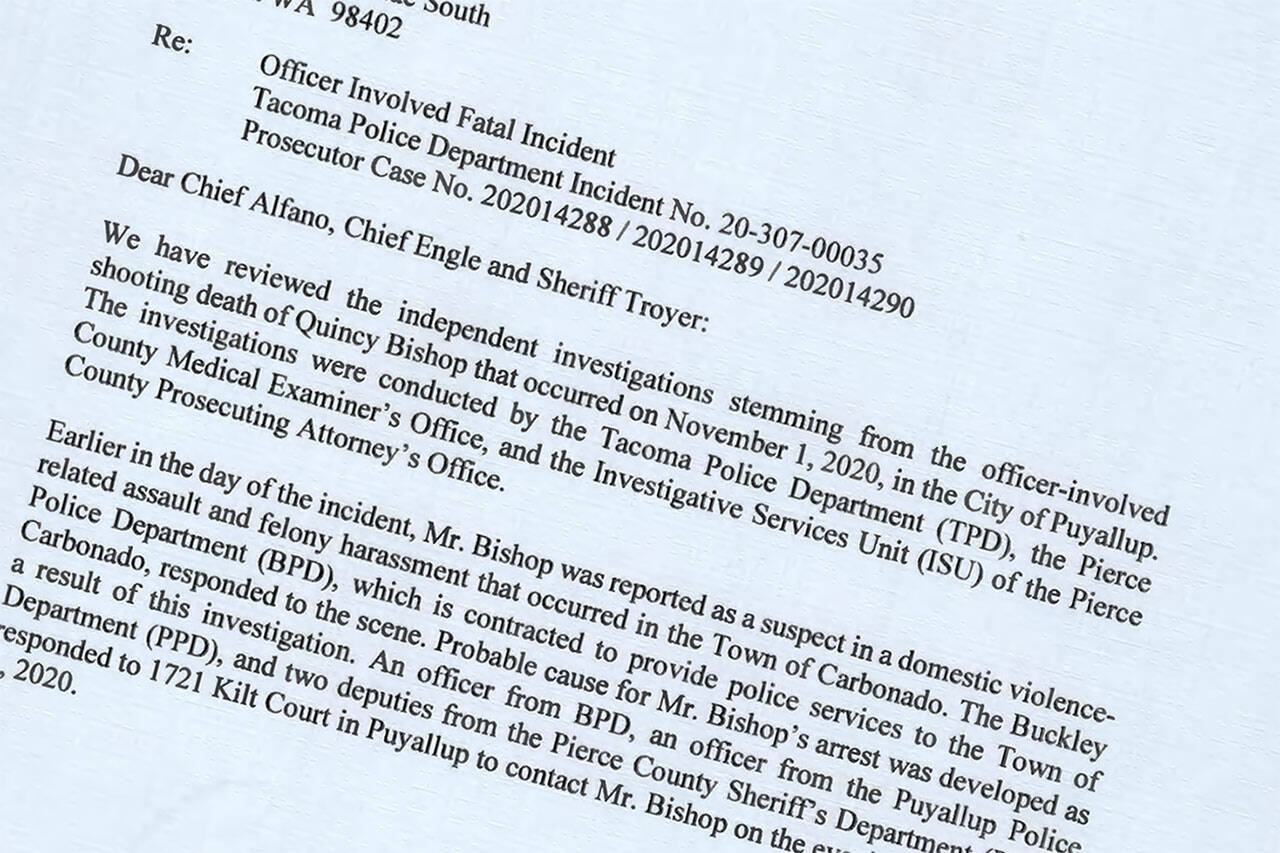

The investigator’s Dec. 28 decision, penned by the Pierce County Prosecuting Attorney, was sent to Buckley PD Chief Kurt Alfano, Puyallup PD Chief Scott Engle and Pierce County Sheriff Ed Troyer, as well as to members of the news media. A full copy of that document is attached to this story online.

The three officers all acted “in good faith” and made a reasonable decision to shoot given the imminent threat to their lives, according to the decision.

The Courier-Herald reached out to Buckley PD for responses to claims from Cory Bishop and the tort claim. However, law enforcement agencies are generally advised not to publicly comment on cases involving litigation against them until those cases are resolved.

In light of those limitations, Chief Alfano said in a phone call that the department is “very happy with the prosecutor’s decision” but declined to comment further due to “the possibility of pending litigation.”

COMPETING NARRATIVES

The report from the prosecuting attorney reconstructs the events leading up to Bishop’s Nov. 1 death using reports of the officers and witnesses involved, though there are several points Cory Bishop strongly disputes.

Bishop had reportedly arrived at his ex-girlfriend’s Carbonado home around 9 a.m., asking to see their two daughters. She told Bishop to leave.

An argument broke out between Bishop and the woman’s current boyfriend, who left the residence to call 911. According to statements given to police, Bishop grabbed a torch attached to a propane tank and threatened his ex-girlfriend that he would “light the house on fire with her and the children inside.”

The woman took the torch away, but Bishop then took a bread knife to her neck and told her he was going to kill her, according to the report. Bishop reportedly cut her left hand when she reached for the knife.

Bishop then took the woman’s cell phone, according to the prosecutor’s report, and drove away. Over a phone call, he reportedly threatened to shoot her new boyfriend and reiterated his threat to burn down the house.

Cory said he doesn’t know what happened that morning aside from what his brother told him, and he didn’t want to disparage Quincy’s ex-girlfriend. But the accusations about his brother’s behavior didn’t sound like the Quincy he knew, Cory said.

Later that evening, Buckley PD officer Arthur Fetter started his shift and his supervisor brought him up to speed on the incident that morning, including the probable cause for Quincy Bishop’s arrest. Fetter knew the Bishops from growing up together in Orting, and was friends with Cory in particular.

“He [Fetter] was the designated driver at my bachelor party,” Cory said. “I worked on his wife’s farm for four years in high school.”

Fetter mentioned to his supervisor that Cory Bishop had contacted him about a month earlier with concerns that Quincy “was having a rough time and had threatened to use his gun if he was contacted by police,” according to the prosecutor’s letter.

Cory recalls that conversation very differently. He said he’d talked about his brother’s problems with his ex-girlfriend, asking Fetter to come out to their house in Carbonado to help defuse the situation.

But “at no point did I say (Quincy) was going to use a gun” if stopped by police, Cory Bishop said.

Fetter’s supervisor, according to the report, then asked if Fetter was willing to try to talk to Bishop and bring him in for questioning. Fetter agreed, believing he’d be less likely to cause a confrontation than another officer.

Fetter and Cory Bishop spoke over the phone that night about the incident at Carbonado. Quincy was living with Cory at his Puyallup house for the time being, and Cory let his brother know the officer would be coming to talk.

The brothers were calm, watching a Christmas movie and getting ready to go to work the next day, Cory said.

“I asked my brother, are you cool with talking with him?” Cory Bishop recalled. “He said he’d give a statement. He told me it’s going to be her word and the boyfriend’s against (his).”

Fetter requested backup on his way there and was joined by three other officers upon arriving at Cory Bishop’s home. (Only three of the four total officers fired their weapons that night.)

That’s a decision Cory doesn’t understand. Cory says Fetter told him he’d be coming alone, just to take a statement from Quincy, and that there was no mention of Quincy being arrested.

Upon arriving, Fetter spoke briefly with Quincy, who said he needed to retrieve his wallet from his truck. Fetter walked to the vehicle as well to keep an eye on Quincy.

Fetter spoke with Bishop for several minutes while Bishop sat in the driver’s seat of his truck. Fetter told Bishop he needed to come to the police station to provide a statement about the incident that morning, and that he wanted Bishop to do so voluntarily, according to the prosecutor’s office report.

According to police, Bishop refused and said he had to go to work. Cory remembers the conversation differently – his brother had work in the morning, not that evening, and so he had asked to drive down to the station himself in case he had to go straight to work from the station, Cory said.

When Fetter then ordered him out of the vehicle, Bishop tried to start the truck, the officers said. Fetter pulled the keys out of the ignition, told Quincy Bishop he was under arrest, and began trying to pull Bishop from the truck with officer Tuell’s help.

Cory said Fetter started the struggle by trying to pull Quincy out. He doesn’t know if Quincy tried to start the car in that struggle, but Cory called it “absolutely false” that he tried to do so before the officers began reaching for him.

Either way, in the ensuing struggle, Quincy Bishop looked down and lifted his sweatshirt, revealing a pistol in his belt line, police say. Quincy then reached down and grabbed that pistol.

Fetter called out “Gun!” and tried to push Bishop’s hand away from drawing the gun. Fetter then drew his firearm, placed it against Bishop’s cheek and told him to stop. However, Bishop continued trying to access his gun, the officers said.

Fetter, realizing he could not keep Bishop’s hand away forever, then fired his gun once, striking Bishop. Tuell also stepped back and fired at Bishop. According to the report, Deputy Calderwood, located at the back of the truck, heard the gunshots, and believing Bishop had fired at one of the other officers, also fired at Bishop. Cory was close enough to the shooting that he recalls his ears hurting afterward.

Fetter retrieved the handgun from Bishop, who was no longer moving, then pulled Bishop from the vehicle with the help of deputy Ashmore. They began performing CPR, but by that point Bishop did not have a pulse.

Emotions were high in the moments after the shooting. Deputy Ashmore recalled hearing Officer Fetter say to himself “f**k, f**k, f**k, I didn’t want that to happen” while performing chest compressions, according to the prosecutor’s letter. Cory was distraught and yelling at Fetter but complied with officers, who put him in a police car.

THE INVESTIGATION

Under state law, officers can only use deadly force if they have no reasonable alternative, and only “in good faith” — in other words, only if another reasonable officer would agree it was necessary to prevent death or serious harm to the officer or someone else.

In this case, there was probable cause for Bishop’s arrest, and he had already made threats to harm or kill others, so the officers were justified in trying to arrest him, the prosecutor found. Furthermore, once officer Fetter realized Bishop was trying to reach his gun and believed that Bishop would try to use it, Fetter was justified in shooting to prevent Bishop from harming him or another officer, the prosecutor said.

Tuell and Calderwood were similarly justified, according to the prosecutor, since they observed the struggle and heard Fetter yell out “Gun!”

”All three law enforcement officers … had a reasonable belief that Mr. Bishop intended to inflict great personal injury upon themselves or other law enforcement officers who were on the scene,” the prosecutor wrote.

Cory Bishop doesn’t see it that way.

He said it was a poor decision from the beginning to have four officers arrive when Fetter said he’d be coming alone. If the officers believed his brother was a dangerous felon who’d threatened to fire at cops, why not arrest him from the start of the interaction, or try to arrest him at work, Cory asked. It’s possible that his brother had a gun in the car, Cory said, but he didn’t remember Quincy having one on his person when they were at the house.

“I want to understand what happened,” he said. “Put aside my brother’s death (and) the exact moment of the shooting. I want to know why (Officer Fetter) did everything that led up to the shooting. … From where I was standing, I don’t believe the use of force was justified.”

Cory acknowledges the prosecutor’s report doesn’t paint Quincy Bishop in the best light: “Was my brother a saint? I wouldn’t say he’s a saint,” Cory said. “I wouldn’t say I am either. But did he deserve to die? No.”

“He had signs of depression,” Bishop added, stemming at least in part from relationship conflicts. “Do I think he wanted to commit suicide by cop? No.”

Cory Bishop said that despite his objection to the way police handled their encounter with his brother, neither he nor Quincy had an anti-cop mindset.

“(Quincy was) a back-the-blue son of two firefighters,” Cory Bishop said. “Conservative. He’s the prototypical Buckley, Enumclaw (kind of guy.) He was a blue-collar, hardworking, back-the-police guy. … He was a hardworking father, loved being outside, loved to go camping, loved to go hiking. He was the life of the party. Did he have his dark days? Sure. I think we all do.”

Cory Bishop hopes that the shooting will be re-reviewed at some level. But ultimately, he also wants to build something positive from the experience and do his part to prevent more deaths like Quincy’s. He’s thought about organizing or getting involved in some kind of group that could connect people to someone who isn’t an armed officer when they need help with a dispute.

“There’s a portion of me that wants to be angry, and be angry forever, and not let this pass,” Bishop said. “There’s another portion of me that I have a six-week old son at home (whom) I have to live for. I can’t have this violence in his world. On either side.”