It was a frigid Friday night in January when Pierce County volunteers left their homes in order to count the homeless.

The more fortunate have a roof over their head during the winter months, as crowded as the space may be.

But hundreds more are forced to face harsh winds, freezing rain and the unrelenting cold without shelter.

And their numbers seem to grow every year.

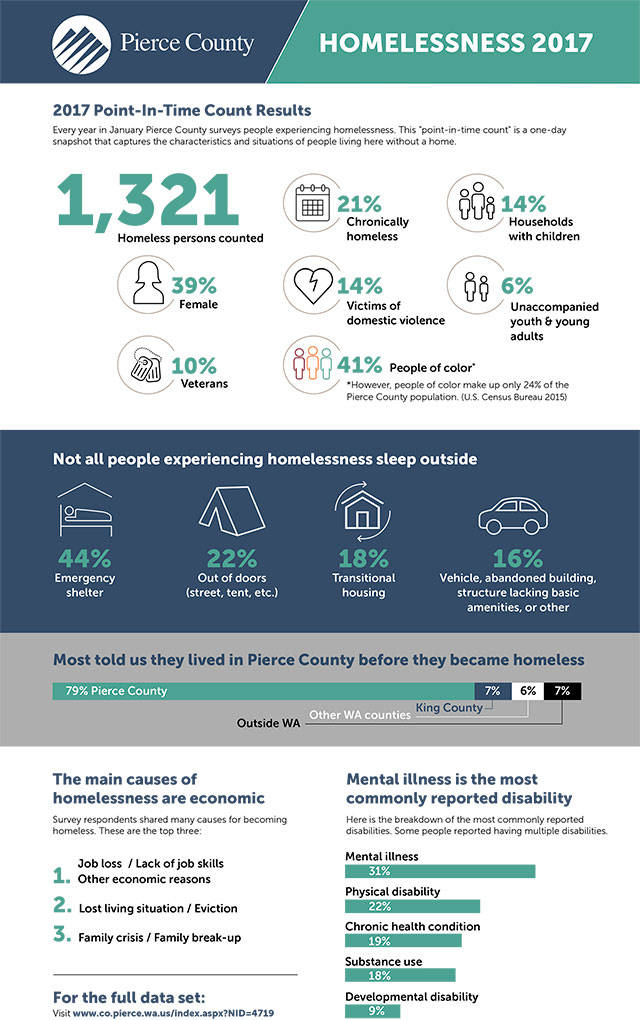

This is Pierce County’s annual Point In Time homeless count, a survey organized by the county’s Housing, Homeless and Community Development Department in order to paint a picture of what homelessness looks like in the area, even if it’s only a snapshot of a single night.

This year, 1,321 homeless residents were counted by 219 volunteers, a 400-person drop from the 2016 count of 1,762 homeless residents.

The survey doesn’t just count whether you’re homeless or not; it also makes the distinction whether you’re sheltered or unsheltered.

This year, 817 residents (62 percent of the total) were considered sheltered, which includes emergency shelters and transitional housing as well as vehicles, abandoned buildings, tents and building overhangs.

This is also a drop from last year, when 1,268 sheltered homeless residents were counted.

The sheltered homeless population has been on the general decline for the past few years, due in part to the county funding permanent housing programs for homeless residents over transitional housing programs, said Tess Colby, the county’s Housing, Homeless & Community Development manager.

This strategy was diverted slightly in 2016, when the county approved a one-time fund to help emergency shelters operate overflow beds during the winter.

Colby said that while 2016 was an anomalous year, the general homeless population is stable with a small increase over the last five years, and the sheltered homeless population is declining.

But what she found “really distressing” was the five-year rise in the unsheltered homeless population.

MORE UNSHELTERED HOMELESS

The 2017 survey counted 504 unsheltered residents, which has risen every year for the past five years, starting at 120 in 2013.

The rise in unsheltered homeless rates could be explained in several ways, Colby said.

One explanation may be that the number of unsheltered homeless residents aren’t rising, but volunteers have the ability to count more of them.

According to the Point In Time survey, the 2017 count had a record-breaking 219 volunteers, as opposed to less than 100 in 2015.

More volunteers, Colby said, means an increased ability to canvas across the county.

“That’s one of the things about the Point In Time count is that weather, the number of volunteers, and the availability in shelter beds all influence what the final count is,” she continued.

But that’s only part of the picture, she continued.

“Particularly starting in 2015, continuing last year and into this year… rents are increasing locally,” she said. “What we find is most people identify economic factors — either eviction, or loss of job, or maybe a family crisis — as the final straw in terms of factors that have resulted in people losing their housing. And certainly that rent is rising at a much quicker pace than wages in our region in an influencer as well.”

According to the state Department of Commerce, rent has been increasing sharply since 2012, noting that urban residents were hit worse, but rural residents were also affected.

“Statewide average monthly rents increased $111 from 2012 to 2015 (from $838 to $949), a 16 percent increase,” the January 2017 “Why is homelessness increasing” report reads. “Rent increases are not necessarily harmful, if incomes increase at the same pace as rents. Although income has been growing in Washington, and growing faster than the national average, income increases for middle and lower incomes have not kept pace with rent increases.”

The report notes that while median rent has increased 18 percent between 2006 and 2015, median income has only increased 3 percent, and low income (the bottom 20 percent of households) is netting out at little to no increase.

The U.S. Department of Veterans of Affairs and the National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans were able to specifically show how rent rates can affect the homeless in the general U.S. population and those already living in poverty.

The data they used were from Point In Time surveys from 447 areas, conducted by The Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2009.

The results, published in the Journal of Urban Affairs, show for every $100 increase in rent, homelessness increases in the general population by 6 percent in cities and nearly 32 percent in non-cities.

And for people already living in poverty, a $100 increase in rent increases homelessness by 14.5 percent and 39 percent in cities and non-cities respectively.

GENERATIONAL POVERTY

Besides sheltered or unsheltered homelessness, the Point In Time survey also records other demographic information like age, race, family status and employment status.

According to the 2017 count, 39 percent of homeless Pierce County residents are female.

About 14 percent of homeless residents are survivors of domestic violence.

Another 14 percent are households with children, while six percent are unaccompanied youths or young adults.

Ten percent of the homeless population in Pierce County are veterans.

The count found 41 percent of the homeless population to be people of color, despite that people of color make up 24 percent of the entire Pierce County population, a statistic that Colby found telling.

“It really brings to light the disproportionately of people who are both living in poverty and also people who are experiencing homelessness,” she said. “We know nationally that African Americans and people of color tend to be overrepresented among people who are very low income, which is to say there is a higher percentage of people of color who are very low income than [the percentage] of people of color in the United States in general. And when you take the next step from living in poverty to losing your house, the disproportionality increases even more.”

Colby said one cause of this are barriers to wealth people of color have been facing for decades – in other words, “generational poverty.”

“One of the things that we know is that when people are about to lose their housing, they turn to family members, they turn to relatives, they turn to friends and their faith communities,” she said. “And if an entire community has much lower wealth available to them — and by that I mean savings accounts or home ownership rates — and there are fewer assets in the community, it makes it much harder for relatives and family members and friends to help out somebody who comes to them.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of people in poverty in the country fell to 43.1 million, or 13.5 percent of the total population, in 2015.

Whites make up 61.4 percent of the total U.S. population and 41 percent of people below the poverty line, based on a total of 318,454 people surveyed for the 2015 Income and Poverty in the United States report.

This is compared to a black population that is 13 percent of the total U.S. population, but is 23 percent of people below the poverty line.

Hispanics are 18 percent of the total population, but 28 percent of people in poverty line.

Asians are 5.7 percent of the total population, and make up 4.8 percent of people living below the poverty line.

The reason why the county made the switch from funding transitional housing to permanent housing, Colby said, is sort of self-evident.

“The thing that ends somebody’s homeless crisis is housing, and transitional housing is just that… you’re still homeless. You don’t have a lease in your name,” she said.

Colby said this trend is country-wide, as communities look closer at how to better allocate resources to help the homeless.

“We can serve and successfully help people end their homeless crisis much more effectively and efficiently if we invest more heavily in permanent housing,” she continued. “And that definitely shows up in the Point In Time count.”

In 2012, 1,805 sheltered homeless residents were counted, which dropped to 1,183 in 2013.

That number dropped further to 942 in 2015.

The number of sheltered homeless residents spiked in 2016, but this year, the number fell down again this year to 817, a seven-year record low.

“Between 2012 and 2016, we’ve been able to increase the number of people who have been able to successfully re-establish housing by over 120 percent,” Colby said. “We’ve more than doubled the number of people that exited programs in 2012 versus 2016.”

King County looks to be jumping on the permanent housing train.

Executive Dow Constantine and Seattle Mayor Ed Murray announced April 3 that a new 0.1 percent sales tax increase in 2018 will fund a task force to propose a strategy that gets homeless residents into permanent homes.

“This region-wide, $68 million per year funding package would replace the previously-proposed, Seattle-only property tax levy,” the press release reads.