The following is written by Keith Seinfeld for Public Health Insider:

If we’re ever asked to consider that we might die someday, most of us probably hope it’s at home or doing something we love.

For people experiencing homelessness in King County, 72 percent die in unfortunate public places, ranging from crawl spaces under buildings, to parked cars, to public parks.

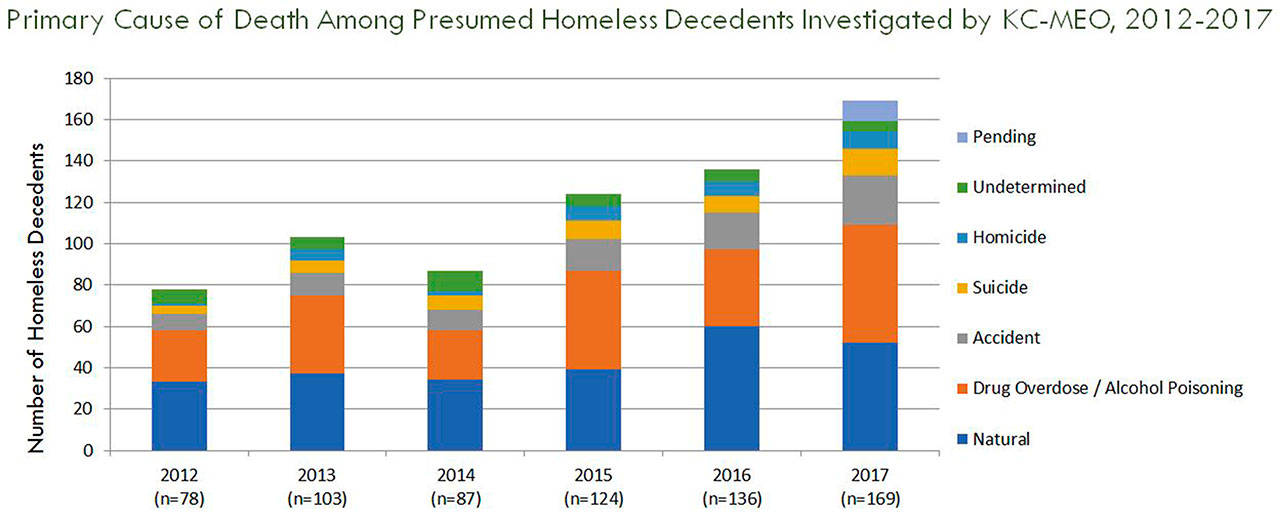

In 2017, the King County Medical Examiner’s Office (MEO) investigated the deaths of 169 people who were homeless at the time. That’s an increase of 32 deaths compared to the previous year — and more than double the number of deaths from six years ago, according to a new report from the MEO.

The increase in deaths parallels an overall increase in the estimated number of people living unsheltered in King County. Approximately half of the deaths occurred outdoors.

Numbers increase, causes remain similar

Among the top killers are drugs and alcohol — together causing 30 percent of the deaths over this five-year period. While opioids (including heroin) caused the most drug-related deaths, the biggest increases have been due to methamphetamine.

Those drug-related deaths have hit especially hard in younger adults who are experiencing homelessness. In this group (age 25-44) — when death is nearly always premature — those who are homeless are far more likely to die than in the general population.

Additionally, “natural causes” account for 37 percent of deaths. These are also the most common killers in the overall population — but they become fatal at younger ages for people with unstable housing. It can be especially challenging for someone to manage an ongoing, chronic condition, such as heart disease when they have no regular home.

This new analysis of deaths occurring in the homeless community reflects a deep dive into death records, to identify people who died while homeless but may not have been counted as such initially. The number of deaths counted is 20 percent higher than previous reports on presumed homeless persons.

Still, the report describes a fraction of all deaths among homeless persons, because it includes only deaths referred to the Medical Examiner’s Office, usually where the cause was unnatural or not determined by a physician.

Strategies to prevent illness and deaths

Information from the report can help enhance strategies that will reduce preventable and premature deaths. For example, King County’s Health Care for the Homeless Network (HCHN) tailors outreach and a wide range of services to meet the specific needs of people experiencing homelessness — aimed at better health outcomes. This network is led by Public Health–Seattle & King County in partnership with nine other medical and behavioral health providers (www.kingcounty.gov/hch).

HCHN and other King County programs are:

- Increasing access to buprenorphine treatment based on the success of Public Health’s pilot project

- working with first responders (housing and shelter providers and local law enforcement) to distribute and use naloxone to reverse opiate overdoses and save lives

- partnering with treatment providers to increase access to same day behavioral health treatment

- opening new detox and treatment beds for youth and adults (2017-2018)

- expanding low barrier mental health and substance use disorder treatment (through street outreach and mobile medical vans)

- providing medication-assisted treatment for people in jail so they can achieve stabilization before release to the community

- seeking to improve integration of primary health and behavioral health care.

Other notable findings from the new “MEO homeless data” report include:

- Geography. Deaths occurred in all parts of the county, with the highest numbers in Central Seattle, Beacon Hill/Rainier Valley and North Seattle/Shoreline

- Race. A higher percentage of those who died while homeless (and investigated by the MEO) were black and Native American people, compared to deaths that occur in the general population.