When are you officially detained by a police officer? The Washington State Supreme Court has ruled that one of the factors is your race and ethnicity — and the way people of certain racial or ethnic groups have historically been treated by law enforcement.

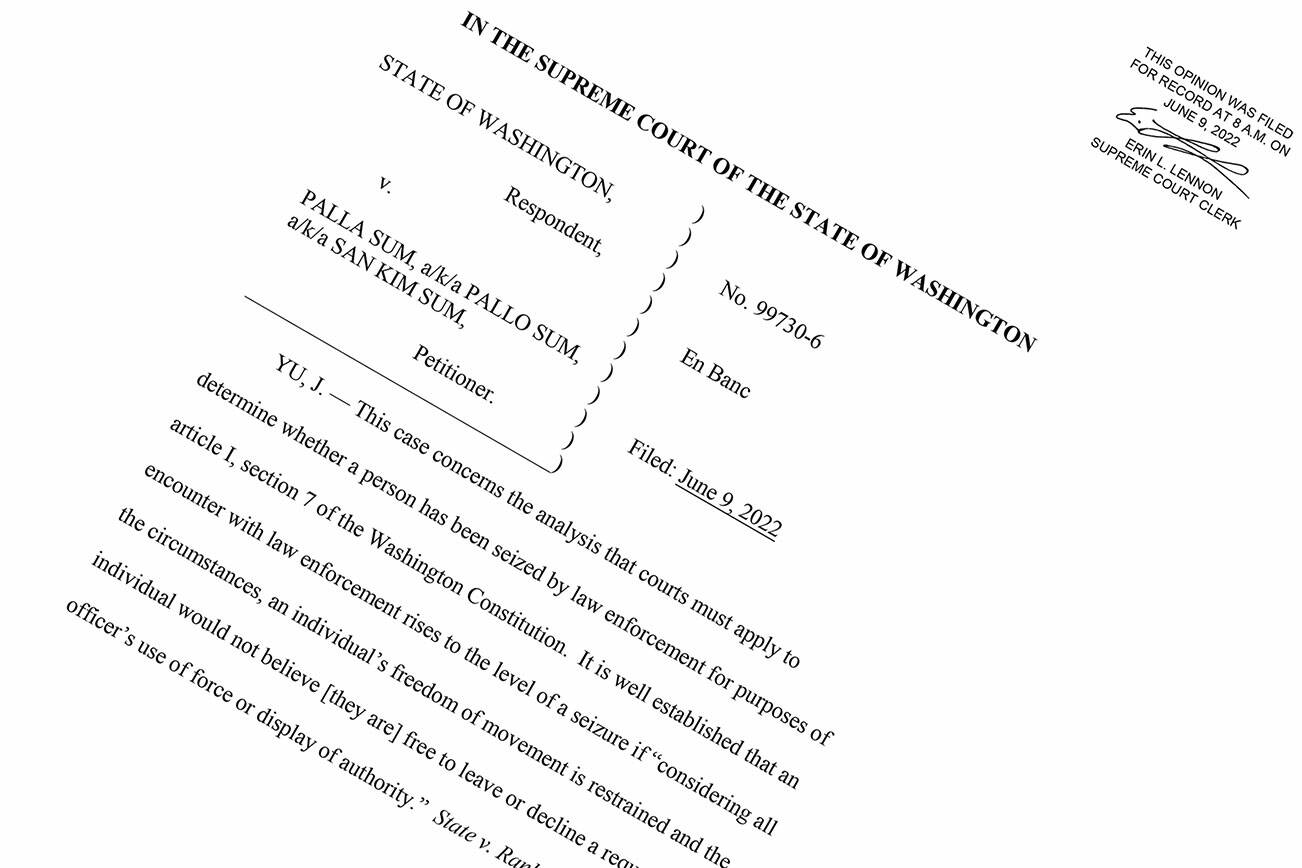

The court’s unanimous ruling on June 9 clarified that police have seized a person — i.e., temporarily stop them from leaving — if an “objective observer” would conclude that the person in question wasn’t free to leave or refuse their requests. And an objective observer would be aware that discrimination and bias has historically led to unfair policing against people of color, the court said.

“We have never stated that race and ethnicity cannot be relevant circumstances,” Justice Mary Yu wrote on behalf of the court in their ruling. “However, we have not explicitly held that in interactions with law enforcement, race and ethnicity matter. We do so today.”

The decision stems from a case in which a Pierce County Sheriff’s deputy stopped Palla Sum, an Asian / Pacific Islander man who was asleep in his car in April 2019 in unincorporated Pierce County. Concerned about car theft in the area, the deputy ran his plates and asked for Sum’s identification.

Sum gave the deputy a fake name and birthdate, and was ultimately convicted for lying to an officer. But he argued in court that those statements aren’t valid evidence because the deputy had “seized” him despite not having a shred of evidence or reason to believe Sum had done anything wrong.

The ruling in Sum’s case wasn’t about whether the deputy in question was racist, or if Sum’s or the deputy’s race made it wrong or right to stop him.

Instead, the court’s decision has to do with how non-white people are scrutinized by police — and how that may make them feel as though they are not free to leave a conversation with a cop even if the officer hasn’t explicitly told them they’re detained.

Both sides in the case — The State of Washington and Pierce County prosecutors on one, and Sum and his attorney on the other — already agreed that race and ethnicity could be relevant to a seizure. To determine that relevancy, prosecutors had asked the court to use the standard adopted by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals: Consider race as a factor only “when the record shows that race was relevant to the encounter.”

But “we decline the State’s invitation to presume that race and ethnicity are irrelevant unless proved otherwise,” Yu wrote.

The court’s ruling didn’t include any specifics from Sum’s case demonstrating how his race actually factored into the stop. Instead, the court found, Sum’s race was relevant by default due to legal precedent and the history of discrimination in the United States toward people of color.

And that ruling in Sum’s case now sets precedent for all other cases in Washington State.

In explaining that ruling, Yu referenced “The Talk,” a conversation that many parents of color have had with their kids about police for generations: Keep your hands where officers can see them. Don’t make sudden moves. Be polite, don’t argue and follow the officer’s orders.

“There is no uniform life experience or perspective shared by all people of color, (but) heightened police scrutiny of the BIPOC community is certainly common enough to establish that race and ethnicity have at least some relevance to the question of whether a person was seized,” Yu wrote.

In other words, a non-white person might feel as if they’re not free to leave a conversation with a cop in situations where a white person would. And if a person isn’t free to leave a stop, the officer legally has to have a good reason as to why they stopped — or “seized” — them.

This fresh ruling may affect how officers approach interactions with the public, especially people of color. It will give judges and juries a point to consider when listening to those criminal cases. And it could be addressed in future state legislation as lawmakers try to balance officer’s abilities to honestly investigate crimes against the harms policing can inflict on vulnerable people.

What does this ruling mean going forward?

“I would say first that police, legal advisors, city attorneys, county prosecutors, they’re going to be absorbing this ruling and thinking about how they advise their clients on changes they need to make in the field,” Pierce County Prosecutor spokesman Adam Faber said in an interview. “That will likely lead to changes in training at the academy and in departments. … Exactly what all those implications are, I don’t think is clear right now.”

In a statement, King County Department of Public Defense Director Anita Khandelwal lauded the court’s decision and said that only reckoning “with the realities of racialized policing” can help society move toward a world where non-white people don’t need to fear police encounters.

“Disproportionate policing, investigative seizures, and the use of force against BIPOC individuals have deeply harmed BIPOC communities,” Khandelwal said. “What’s noteworthy is the Court’s recognition of this reality. It’s not often that our clients have their truths lifted up in this way.”

Prosecutors in the case warned that the standard adopted by the Supreme Court would prove confusing for police and judges.

“Unfortunately, this decision will likely further confuse law enforcement officers about their interactions with the public,” in a statement, Pierce County Prosecuting Attorney Mary Robnett said in statement. “Police officers and trial court judges, especially, are facing some confusing and uncertain times ahead as they try to correctly apply the court’s ruling.”

The Courier-Herald has reached out to Sum’s attorney for comment.

THE CASE

The ruling stems from an April 9, 2019 encounter between Palla Sum and Pierce County Sheriff’s deputy Mark Rickerson.

Rickerson was patrolling in Pierce County when he noticed a Honda Civic parked near the entry gate to a church parking lot. Although the Honda wasn’t blocking the entry gate and didn’t appear to be parked illegally, Rickerson was concerned since there had been vehicle thefts in the area.

Rickerson noticed Palla Sum slumped over in the Honda and parked nearby, making sure not to block Sum’s car. He ran the Honda’s license plate first; the car wasn’t reported stolen, but the records didn’t say who owned it.

Rickerson knocked on the driver’s window, asking Sum for his identification and pointing out he was sitting in an area “known for stolen vehicles.” According to court documents, the deputy said Sum told him the vehicle didn’t belong to him.

Sum then gave the deputy a fake name and birth date. When Rickerson returned to his vehicle to check that information, Sum started the Honda and sped off, running several red lights and ultimately crashing in someone’s front yard.

Sum was arrested. A search turned up the Honda’s title and registration, which showed the car did belong to Sum, who had purchased it only two weeks earlier. Deputies also found a pistol in the car.

Sum argued in court that Rickerson unlawfully stopped him without reasonable suspicion of a crime, but the trial court ruled that Rickerson didn’t seize him when he asked Sum to identify himself. Sum was convicted by a jury of unlawful firearm possession, trying to elude an officer and making a false statement.

Sum appealed that ruling, but the appellate court agreed with the trial court, finding again that “merely asking for identification is properly characterized as a social contact” as opposed to an brief detainment.

Sum petitioned to the Supreme Court, arguing the law should consider the effect of race during police contacts.

If you see an officer stop someone on the street, put a hand on their shoulder, flash a badge and tell them they’re not free to leave, it would be reasonable to assume that person had been “seized” temporarily. But in other situations, it might not be so clear.

So at question for the Supreme Court was this: Are race and ethnicity factors in those situations?

The justices said yes.

Sum didn’t deny that the Rickerson’s initial contact was reasonable. But the deputy didn’t have a warrant or reason to believe a a crime was underway, and the state — representing Rickerson — conceded that there was no lawful reason to seize Sum until he sped off in the car.

The State of Washington argued that Sum didn’t provide any evidence that Pierce County officers were more likely to discriminate or be violent against Asian or Pacific Islander people, or that Rickerson was influenced by Sum’s race. Plus, the court has ruled before that a person isn’t seized just because an officer talks to them in public and asks them for identification.

But at the point where Rickerson asked Sum for his ID and mentioned frequent car thefts in the area, the encounter had turned into a seizure, the court decided: “At that point, it would have been clear to any reasonable person that Deputy Rickerson wanted Sum’s identification because he suspected Sum of car theft.”

“In other words, an objective observer could conclude that Sum was not free to refuse Deputy Rickerson’s request due to the deputy’s display of authority. At that point, Sum was seized. As the State correctly concedes, this seizure was not supported by a warrant, reasonable suspicion, or any other authority of law.”

Since the stop wasn’t legal, the court found, Sum’s fake name and birthdate must be suppressed — i.e., they aren’t valid evidence in a court. The court reversed the Court of Appeals decision and sent the case back to the trial court level, where Sum’s fate in court will continue.

Sum’s other two convictions — attempted eluding and unlawful firearm possession — were unaffected by the Supreme Court ruling, and Faber said the Pierce County prosecutor doesn’t plan to retry the misdemeanor false statements case against him.