Mental illness doesn’t affect everyone, but it affects more people than any one person might realize.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness estimated 219,000 adults in Washington state suffer from a serious mental illness, as well as 71,000 children.

It’s a serious issue; some might say it’s no laughing matter. But Sara Benincasa would disagree.

“Probably the most common criticism I receive is from people who don’t think I should be using humor to talk about this serious issue,” Benincasa said.

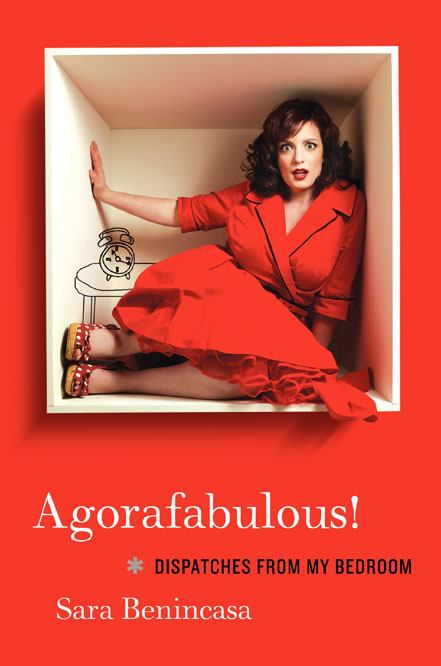

Benincasa is a stand-up comedian and writer for publications like Wonkette, xojane.com, the Daily Show Indecision blog and Jezebel. She recently published “Agorafabulous!: Dispatches From My Bedroom,” a memoir about a decade of her struggles with agoraphobia and anxiety. The book spans the time periods from her first serious panic attack as a teenager to a mental breakdown in college that rendered her unable to leave her apartment and bed, to the subsequent years of recovery, speed bumps and personal growth.

“I subscribe to the notion that if you can laugh at the (worst) moments in your life, you can transcend them,” she writes in the book’s foreword. “And if other people can laugh at your awful (moments) as well, then I guess you can officially call yourself a comedian.”

“Agorafabulous” is Benincasa’s literary debut, but it carries a confidence and clarity of voice one might expect from an oft-published author. It’s sad, insightful and funny all at once, and yet the combination never feels contradictory.

My personal favorite chapter of the book dealt with Benincasa’s brief employment as a personal assistant to the loose cannon owner of a new age retreat in rural Pennsylvania. The story takes place relatively early in her recovery and she successfully manages to reproduce her utter confusion and fear. Confusion over whether it’s normal for a full-grown man to have so many mood swings in one day, and fear at being deemed a failure if she quit.

Benincasa took some time from her busy schedule to sit down and chat about her book.

Daniel Nash: Your book is an adaptation of a one-woman show you did originally, yes?

Sara Benincasa: Yeah! I did a show called ‘Agorafabulous’ and it was anywhere from 30 to 80 minutes depending on the venue, and I just retold my story. It’s interesting to have translated it from a live comedy show to a longer and somewhat serious book.

DN: Is there stuff in the book that wasn’t originally in the show?

SB: Oh definitely, yeah. There was so much going on in the story that to boil it down for theater I really had to discard a lot and I was able to really expand it in writing the book… I think just the right amount. I don’t think I included too much, I think I put in just the right amount.

DN: You talk about having a number of mental illnesses, but you generally group them under the umbrella term agoraphobia. Would you like to talk about those a bit?

SB: Sure; they’re fun. I have panic disorder, which entails panic attacks which are discrete, as in d-i-s-c-r-e-t-e. They’re also the other kind of discreet—you can’t always tell when someone’s having one—but they are discrete events you can kind of point to on a timeline and say, ‘I had a panic attack there, I had a panic attack there, it lasted two minutes, it lasted 30 minutes, it lasted an hour.’ And, of course, along with that comes generalized anxiety disorder—which is also fun—which is a more general, constant hypervigilance, worry and concern. And then there’s agoraphobia, which is really an advanced version (of anxiety). Agoraphobia is a fear of travel, it is a fear of crowds; it translates directly to ‘fear of the marketplace’—agora is marketplace in Greek—and it’s funny because I live here in Queens where there’s a big Greek population, so there’s a lot of stores called ‘Agora.’ So, for me, it usually manifests itself as a fear of traveling, and sometimes a fear of crowds, and it can be so crippling over time that eventually some people become restricted to their homes. And that is what happened to me.

DN: In college. Chapter 3 deals with you going to Emerson College, and then by your junior year you were full-on agoraphobic and couldn’t leave your apartment.

SB: Yeah. Chapter 3 is called ‘Bowls of Pee,’ because in Chapter 3 you get to read about a very unsavory time in my life, when I had really painted myself into a corner. I was so frightened I didn’t leave my apartment, but more than that I was too scared and often too depressed to leave my bed. And I had to pee somewhere, so… You know, it was a heavy time, it was a scary time, and it was something I didn’t really talk about until a few years ago just because it had never occurred to me to talk about it. I don’t think I thought it was normal, but I think I was so used to it being a part of my history that it didn’t occur to me to talk about it. And also because, you know, it’s disgusting and embarrassing, so why would I bring it up?

DN: Well, I think, even though it seems extreme in retrospect, I think even though your story isn’t something everyone can relate to, it’s something more people can relate to than any one person might suspect.

SB: I hope so. My aim for writing the book was for someone to be able to read it whether or not they suffered from agoraphobia or panic attacks, and feel a sense of kinship, a sense of comfort in whatever type of loneliness they’re experiencing, whether or not it’s of the clinical sort.

DN: You had, from what you’ve described, a great support system in your family. And you’ve said on your podcast, “Sex and Other Human Activities,” that your father works in pharmaceuticals. Your family has some familiarity with mental illness and the proper medications. Do you think you had an advantage in recovery in that regard? Has that given you a better perspective on the issue if somebody talks to you about their own issues with mental health?

SB: Um, sometimes. That, I think, comes from being in therapy. To an extent, knowing about the way certain conditions tend to present—for example, schizophrenia and bipolar tend to present themselves in the late teens and early twenties—but if somebody starts to talk about certain symptoms I recognize from certain disease states I heard about growing up with a family in pharmaceuticals… It’s not like I’m going to diagnose somebody, but I know enough that I can say, “If you’re seeing things that aren’t there, if you’re hearing things that aren’t there, then this might be something to talk to a therapist about.” But I suppose anybody would say that.

But I think the biggest thing that I got out of it was money. I come from a family that works in an industry that makes a load of money. Not that my family makes a load of money, but the industry makes a load of money—Big Pharma is big for a reason. It is sometimes corrupt, it is sometimes wonderful. It saves lives, and in our country, due to a number of factors, some drugs are extraordinarily expensive. I take a drug called Abilify that is an atypical antipsychotic I take in combination with Prozac; it’s kind of a booster. If I did not have health insurance, it would be $500 a month just for Abilify. Now, are there some pharmacies where it might be available for $400 a month? Sure. But that’s still a load of money.

So I think I grew up around that conversation about disease states and what they look like, but the most important thing is that I grew up with health insurance. With a dad who worked at a big company for many years, a traditional, old-fashioned corporation that provided health insurance for workers and their families, and health insurance from my mom because she worked as a public school teacher. That’s it: I had access. The difference between me and a girl who commits suicide at 21, and someone who is homeless and unemployable because of their untreated mental illness, is money. I don’t have a strength or fortitude that those people don’t have.

If I could write the book over again, that is a message I would make abundantly clear.