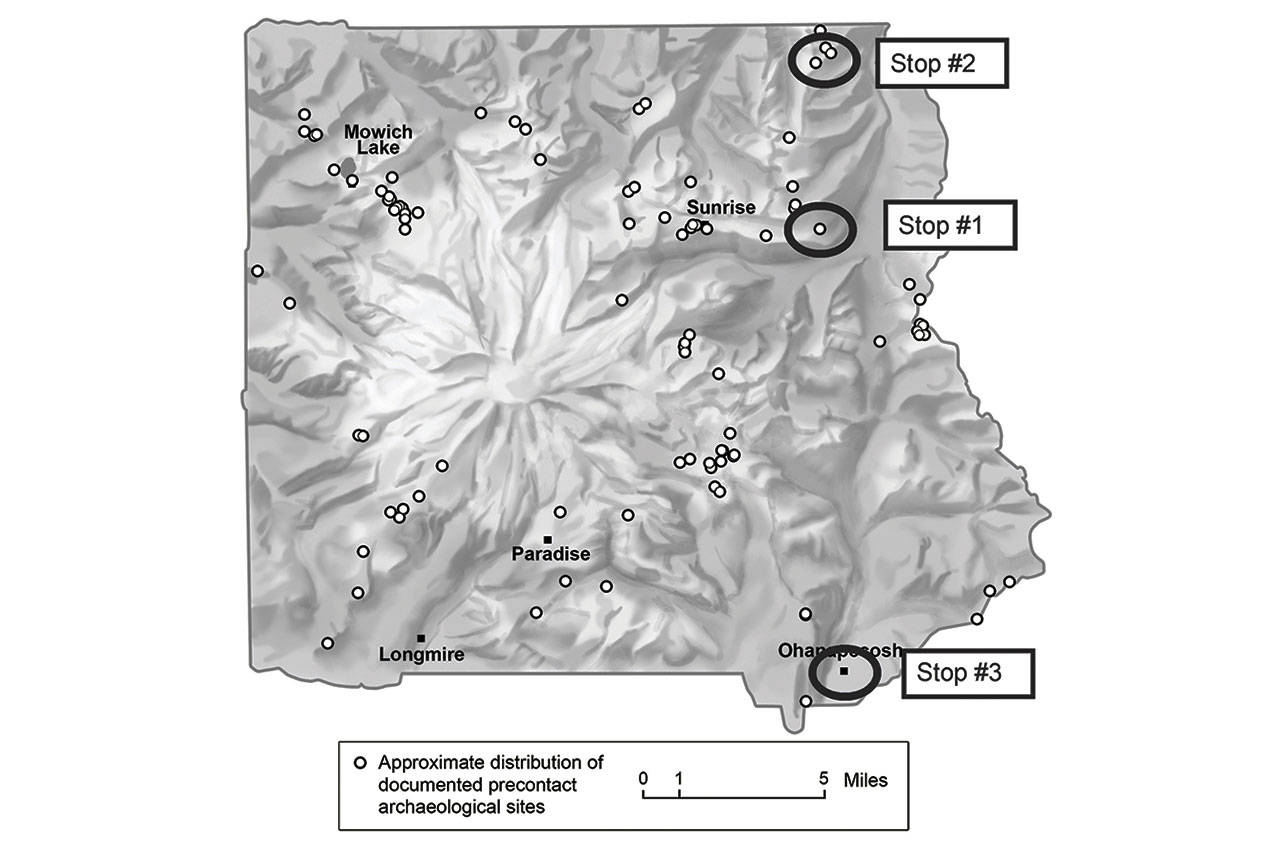

In November’s column, we saw that the excavation of a 1,000 year-old hunter’s camp along Fryingpan Creek on Mount Rainier’s northeast side provided proof that Native Americans had traveled to the mountain for generations. The find didn’t stamp out the mistaken idea that indigenous people avoided the high country, but the ensuing 30 years of diligent work by archaeologists and tribal experts would eventually reveal a robust portrait of peoples’ relationship with Tahoma (one of several Native names for the mountain). In today’s column, we’ll take a virtual field trip to visit some of Mount Rainier’s most important archaeological locations. So lace up your hiking boots, grab your daypacks, and let’s go!

Our first stop is on the mountain’s north side, partway up to Sunrise from the White River Campground. In 1990, Richard McClure Jr. found stone tool artifacts eroding out of this side hill. Among them was a stone fashioned as a hammerhead, grooved around its midsection to accommodate strapping to hold a handle in place. Subsequent digs by Central Washington University’s anthropology field school recovered thousands of stone tools and found some intriguing site features: gentle depressions in the ground may have been sleeping areas, and fire hearths held charcoal and bits of bone and teeth, along with fire-preserved plant materials. Later lab analyses determined that people had roasted mountain goats, marmots, and grouse here, and had eaten huckleberries and whitebark pine nuts. Researchers determined that this area was an ancient campground, over 4,000 years old.

Based on its location, it’s likely that people living on the Green and White rivers—ancestors of present-day Muckleshoot tribal members—camped here in midsummer after the snows receded and the weather warmed. It’s also probable that Yakama forebears made the 80-plus mile trek from their lowland villages.

All right, everyone, back on the bus—we’re off to our next stop!

After a short hike in the Slide Mountain area in the northeastern portion of the park, we come to this unnamed lake, one of Mount Rainier’s most fascinating archaeological sites. Excavated over several seasons, this age-old camp yielded over 20,000 stone tool artifacts. The lake’s location within Muckleshoot traditional use areas makes it reasonable to assume that Muckleshoot ancestors frequented the site. The tribe, in fact, provided logistical support for the project. In addition to the vast number of recovered items, the age of some—exceeding 9,000 years—places this gem of a lake as one of the oldest known locations of human use at Mount Rainier National Park.

The number and age of the artifacts recovered, along with the collaboration with a tribal community, makes this excavation a high water mark in the career of Greg Burtchard, who directed the dig. Burtchard’s tenure at the park began as a contractor in 1995 when he and colleague Stephen C. Hamilton conducted field reconnaissance on 3,500 acres within the park. They added an astonishing 32 finds to the park’s nascent archaeological record, resulting in Burtchard’s hiring as the park’s first archaeologist. His 1998 report, Environment, Prehistory & Archaeology of Mount Rainier, Washington, is the seminal story of indigenous people venturing onto Mount Rainier’s flanks. Burtchard’s ideas about the “where and when” that people went to the mountain, and how their use patterns changed over time, continue to guide the trajectory of this type of fieldwork at Mount Rainier.

Now, hop back on, everyone, we’re off to our last stop—the Ohanapecosh Campground!

Our first two stops on today’s field trip, like most of Tahoma’s sites, were in or near subalpine meadows. These lush blankets of mostly treeless flower fields ring the mountain from 4,000 to 6,600 feet in elevation. Considering that people traveled for days on foot to get to Mount Rainier (travel by horseback began only in the last several hundred years), why did they then climb partway up the mountain—why not camp in the lowland areas? The answer lies in the ground, literally. Plants valued for medicinal and technological uses, like pipsissewa and bear grass, and food plants that included huckleberries and others, don’t grow well in the deep and ageless forests, but more so in the open subalpine areas. Game animals that include bear, deer, elk, and others forage in these areas, increasing a hunter’s chances of success. Also, camps at those elevations are adjacent to higher ground for hunting the much-prized mountain goat. So even after several days of trekking, hiking a few more miles—even uphill—to be closer to their target resources made perfect sense.

But here at the Ohanapecosh Campground, we stand in the shade of an old growth forest, not in the brilliant sunlight of the meadowlands. Before installing underground utility lines, federal regulations required the park to survey the grounds for cultural resources. Remarkably, the crew found stone tool fragments, scrapers, and projectile points at more than a dozen sites that dated back over 7,300 years. Without easy access to upland resources, why did people camp here? It was a puzzle for Burtchard and his staff to solve. Knowing that peoples’ primary draw to the mountain was to gather resources unavailable or in short supply near their homes, Burtchard reasoned that people made short-term camps here as they traveled between the mountain’s upper slopes and their Yakama, Klickitat, or Upper Cowlitz villages.

As we wrap up today’s virtual field trip, readers should know that the park continues its collaboration with local tribes, with park archaeologist Ben Diaz serving as tribal liaison. Currently, there are over 100 sites scattered around the mountain as we keep learning about the legacy of Native Americans at Tahoma.

In next month’s column, we’ll move into contemporary times and profile modern day Mount Rainier old-timers. If you have a backlog of mountain stories or know someone with a rich Mount Rainier history, I’d like to hear from you. In the meantime, keep your boots dry and your spirits high.

Jeff Antonelis-Lapp is an educator, naturalist, and writer living in Enumclaw since 1982. Tahoma and Its People, his natural history of Mount Rainier National Park, was published this spring by Washington State University Press. Copies are available at https://jeffantonelis-lapp.com/. Jeff would love to hear from you about Mount Rainier. Send your questions and favorite stories to rstill@courierherald.com, and subscribe to his blog, too.