As a follow up to last week’s article from the Washington Department of Ecology, this month I am writing in support of a powerful anti-litter program that is used in ten other states, including most of the Northeast.

Living in Connecticut means living with a “bottle bill”. Buying a bottle or can of beer, soda, water, or juice means paying a five cent deposit on each container. Most households have a place where they collect the empty bottles and cans, which are then returned to the store, and the deposit is paid back to the consumer.

The deposit law went into effect in 1980. We were used to it. There were some shelves in the garage where the empties were collected, and when the shelves were full, the old drink containers went into the car and back to the store. Was it a nuisance? Sure, but after living with the deposit law for most of my adult life, I accepted it.

It seemed that most people had a system of some kind. I think it is often true that people buy their favorite sodas or beers in fairly large quantities, like 12 packs or 24 packs. Friends of mine would buy their favorite beer in 30 packs, and put the empty cans back into the cardboard case. When it was full, they would return it to the store, and buy another 30 pack. Their deposit refund covered the deposit on the new case. No big problem.

But, when we moved to Enumclaw, I was pretty happy to toss beer cans into the regular recycling bin and have it picked up by the city. I didn’t miss that shelf in the garage with the empties. I didn’t miss bringing them back to the store.

When the Bottle Bill was passed in Connecticut, it had the stated purpose of reducing litter. With a small financial incentive to return the cans instead of leaving them behind or tossing them out the window, it seemed that people would be less likely to litter. For those containers that were not properly disposed of, there would be an incentive for other people to collect and return them. It achieved this goal well enough that there is little resistance to the bottle deposit laws. In fact, the deposit will be increased on Jan. 1, 2023.

I used to spend a lot of time jogging or bicycling, and I would always notice any litter on the side of the road. I never actually counted up cans per mile or anything like that, but I felt certain that states without beverage container deposits had more bottles and cans on the roadsides.

I expected that, in a place of such great natural beauty and with a tradition of outdoor recreation, I thought that Washington might be an exception to my observation that states without bottle deposits have more roadside litter. This did not turn out to be true. The roadside litter around here is visibly worse than what we were used to seeing in Connecticut.

It isn’t just roadsides that collect litter. Enumclaw Golf Course is also a spot for the lazy and irresponsible to leave their cans behind. Really? You can carry a full can in your bag, but then when you empty it you can’t put it back in the bag? You would rather toss it in the brush?

Unfortunately, the Washington state “bottle bill”, otherwise known as the WRAP Act, died in committee during the last legislative session, likely meaning little to no improvement in our garbage problems.

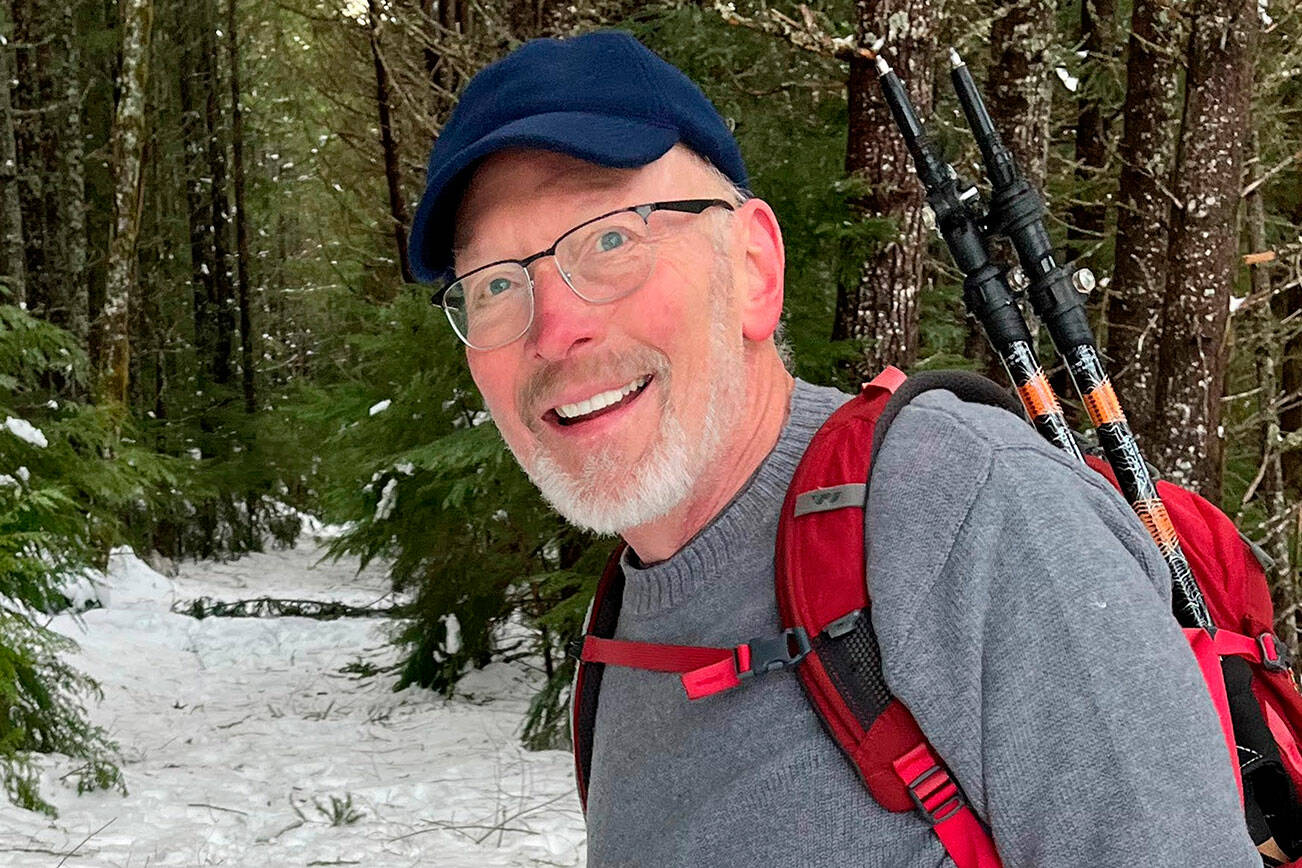

On Saturday morning I collected trash from along the roadside on SE 472nd street near the Cal Magnusson Trailhead.

I suppose that walking around and picking up trash seems a little bit odd, but I have encountered other people doing similar things. I’m impressed by the people who anonymously clear blowdowns from the trails at Mount Peak. I have my limits as to what I will collect, too. There are things I won’t pick up. The three urine filled bottles tossed in the weeds along 472nd street are still there, for instance. Seriously man, (I am pretty certain this was not done by a woman) there is even a public outhouse at the trailhead!

I walked about a quarter mile in one direction, and then back again, filling two garbage bags as I traveled. Those two bags contained 83 beverage containers that would be covered by the deposit laws in Connecticut. The other 33 items were mostly food wrappers, and a few coffee cups.

These items were generally smaller than the beverage containers, which really made up the majority of the volume of trash. I don’t know how my results compare with the results cited by the Department of Ecology, and I don’t pretend it accurately represents the whole state, but it certainly squares with our rough observation – Washington has a litter problem, and it would be improved by passing a beverage container deposit law.

Several studies have shown that deposit laws do reduce the accumulation of litter, although the results of the studies do vary quite a bit. The EPA found that litter was reduced by 40%, the Natural Resources Defense Council found a reduction of 69%, and the State of Michigan found a reduction of 80%. All of those numbers seem significant to me. Deposit laws work to reduce litter.

The inconvenience that consumers have to put up with in deposit states is nothing compared to what the merchants experience. The stores that sell the beverages have to collect the returned containers and give them back to the distributors. An old friend, who worked a part time job in a Connecticut liquor store before being promoted to manager of the store and eventually to a regional sales job with a distributor, recalled his time processing returns as “one of the most miserable tasks imaginable”. Stacking all the varying sizes of containers was a challenge, but the biggest aggravation came from customers who did nothing to clean their empties before returning them.

While cleaning out the case of Mexican lager bottles, “Each with a moldy lime wedge and a cigarette butt inside”, he would realize “deposits do work”. The same customer who returned the dirty bottles would be the person who would gladly toss the bottle out the car window, except they can’t tolerate the thought that “then someone else will keep their money”. Even ignoring the benefits of recycling, he wrote, “if a small deposit on a can or bottle can trick people into not throwing their bottles where they want, then dealing with some dirty empties is a small price to pay.”

I can imagine some readers getting angry at this opinion. It may seem unfair that people who never litter have to pay the deposit just because a few irresponsible people throw cans on the roadside. It may seem to some that this is part of some liberal plot to control people’s behavior. It may even seem to someone that this is an attempt to reduce beer drinking.

I don’t intend anything like that at all. If you’d like to talk about it, we could meet somewhere. I’ll buy you a beer.